College Readiness of California’s

High School Students

The State Can Better Prepare Students for College by

Adopting New Strategies and Increasing Oversight

Report -

February

COMMITMENT

INTEGRITY

LEADERSHIP

For questions regarding the contents of this report, please contact MargaritaFernández, Chief of Public Affairs, at ..

This report is also available online at www.auditor.ca.gov | Alternate format reports available upon request | Permission is granted to reproduce reports

Capitol Mall, Suite | Sacramento | CA |

CALIFORNIA STATE AUDITOR

.. | TTY ..

...

For complaints of state employee misconduct,

contact us through the Whistleblower Hotline:

Don’t want to miss any of our reports? Subscribe to our email list at

auditor.ca.gov

Doug Cordiner Chief Deputy

Elaine M. Howle State Auditor

621 Capitol Mall, Suite 1200 Sacramento, CA 95814 916.445.0255 916.327.0019 fax www.auditor.ca.gov

February 28, 2017 2016-114

e Governor of California

President pro Tempore of the Senate

Speaker of the Assembly

State Capitol

Sacramento, California 95814

Dear Governor and Legislative Leaders:

As requested by the Joint Legislative Audit Committee, the California State Auditor presents this

audit report concerning access to and completion of college preparatory coursework needed for

admission to the State’s public university systems.

Our analysis suggests that students attending school districts that establish higher student expectations,

coupled with relevant tools and student support, are more likely to meet those expectations. SanFrancisco

Unified School District’s (San Francisco) college preparatory coursework completion rates (completion

rates) were significantly higher than the other twodistricts we reviewed—Stockton Unified School District

(Stockton), and Coachella Valley Unified School District (Coachella). Specifically, in2015 only 21percent

of Stockton’s students successfully completed the college preparatory coursework, while 30percentof

Coachella’s students met these requirements. In contrast, 69 percent of students in San Francisco

completed college preparatory coursework. We believe the difference in completion rates is in part because

SanFrancisco requires its students to take college preparatory courses in order to graduate and has devoted

significant resources to assisting its students in thisendeavor.

We also found that completion rates are influenced by whether students stay on a prescribed track

each year—most notably in grade nine. At each of the three districts, we found most students who

fell off track for completing the necessary coursework did so during gradenine and only 9percent of

them went on to complete the coursework necessary to gain admittance to the State’s public university

systems. us, students’ academic preparedness upon entering high school significantly impacts

completion rates. Funds to help kindergarten through grade eight students prepare for the rigor of

college preparatorycoursework could help keep more high school students on track to complete college

preparatory coursework requirements by their senioryear.

In addition, our review indicates that schools within our selected districts were able to provide students

with sufficient access to college preparatory coursework during the years that we reviewed, but we

encountered significant barriers to assessing the level of access because of the limited data the districts

maintained. e California Department of Education and county offices of education could provide

additional oversight, support, and guidance to districts to ensure they provide sufficient access to college

preparatory coursework and adequately assist their students in completing thosecourses.

Respectfully submitted,

ELAINE M. HOWLE, CPA

State Auditor

Blank page inserted for reproduction purposes only.

vCalifornia State Auditor Report 2016-114

February 2017

Contents

Summary 1

Introduction 5

Chapter 1

School Districts May Be Able to Significantly Improve Students’

CollegeReadiness by Offering a Range of Academic Supports 13

Recommendations 39

Chapter 2

Increased State and County‑Level Guidance and Oversight

CouldImproveStudents’ College Preparedness 41

Recommendations 51

Appendix A

Our Analysis of Student Access to College Preparatory Coursework 53

Appendix B

Student Demographics of Three Selected Districts 57

Responses to the Audit

California Department of Education 61

California State Auditor’s Comments on theResponse From

the California Department of Education 65

Coachella Valley Unified School District 67

California State Auditor’s Comment on theResponse From

the Coachella Valley Unified School District 69

Stockton Unified School District 71

vi California State Auditor Report 2016-114

February 2017

Blank page inserted for reproduction purposes only.

1California State Auditor Report 2016-114

February 2017

continued on next page . . .

Audit Highlights . . .

Our review of three school districts’

efforts related to college preparedness

highlighted the following:

» College preparatory coursework

completion rates were significantly

higher—69 percent—in one school

district compared to those in the other

two districts—21 and 30 percent.

» Completion rates at the three districts

we reviewed were heavily influenced by

students’ ability to complete coursework on

a prescribed track beginning in grade nine.

» The vast majority of students in two of

the three districts fell off track during

some point in their high school careers

and very few of those students went on to

complete college preparatory coursework.

» Although our analysis suggests that our

selected schools were able to provide

students with sufficient access to college

preparatory coursework during certain of

the years we reviewed, we encountered

significant barriers to assessing the level

of access for all years because of the

limited data the districts maintained.

» All three districts we reviewed showed

achievement gaps in completing college

preparatory coursework between certain

subgroups of students; however even

similar subgroups of students, such

as English learners, fared better in

one district compared to the other two.

» One district has devoted significant

resources to help its students, including

providing targeted intervention and

support for students who are not on track

to meet requirements.

Summary

Results in Brief

In recent years, California’s state and local educational agencies

have increasingly focused on the importance of preparing the

State’s students for college. e Public Policy Institute of California

projects that percent of California’s jobs will require at least a

bachelor’s degree by, while population and education trends

suggest that only percent of working-age adults in California

will have a bachelor’s degree at that time—a shortfall of .million

college graduates. To fill this gap, the State will need to significantly

increase the number of college-ready students who graduate from

its high schools each year. Onemeasure of college readiness is a

high school student’s completion of the college preparatory courses

necessary for admission to the University of California (UC) and

California State University (CSU). In – less than half of

high school students statewide completed the college preparatory

coursework that would qualify them to enroll in a UC or CSU

school upon high schoolgraduation.

Of the three districts whose efforts to improve college preparedness

we reviewed—SanFrancisco Unified School District (SanFrancisco),

Stockton Unified School District (Stockton), and Coachella Valley

Unified School District (Coachella), we found that SanFrancisco’s

college preparatory coursework completion rates (completion

rates) were significantly higher than those of the other twodistricts.

Specifically, in only percent of Stockton’s students and

percent of Coachella’s students successfully completed college

preparatory coursework. In contrast, percent of students

in SanFrancisco completed college preparatory coursework.

Although a number of factors contributed to the differences

in the threedistricts’ success in preparing students for college,

SanFrancisco’s prioritization of college preparatory coursework

completion appears to have a significant impact. In

SanFrancisco aligned its graduation coursework requirements with

the minimum coursework requirements necessary for admission to

UC andCSU.

Completion rates at the threedistricts we reviewed were also

heavily influenced by students’ abilities to complete coursework

on a prescribed track beginning in gradenine. Falling off this

track significantly decreases students’ chances of completing

college preparatory coursework. e vast majority of students in

graduation years through in Coachella and Stockton

fell off track at some point during their high school careers and

few of those students went on to complete all the necessary

college preparatory coursework by the end of high school.

California State Auditor Report 2016-114

February 2017

2

Specifically, percent and percent of Coachella and Stockton

students, respectively, fell off track and only percent of

Coachella and percent of Stockton students completed college

preparatorycoursework.

At each of the threedistricts, we found that of the students who fell

off track for completing the necessary coursework, up to percent

did so during gradenine, indicating that districts should ensure

that students enroll in and compete college preparatory coursework

beginning in their firstyear of high school. Furthermore, an average

of only percent of the students who fell off track in gradenine in the

threedistricts we reviewed graduated with the coursework necessary

to gain admission to the State’s public university systems. Moreover,

we found that on average, percent of Stockton students, percent

of Coachella students, and percent of SanFrancisco students did

not pass a college preparatory English class by the end of gradenine.

e percentage of gradenine students who were not prepared forthe

rigors of college preparatory coursework suggests that equipping

kindergarten through gradeeight students with the necessary skills

and knowledge is critical to ensuring that they will graduate from

high school having met the coursework requirements for admission

to the State’s public universitysystems.

Although our analysis suggests that the schools we selected were

able to provide students with sufficient access to college preparatory

coursework during certain of the years that we reviewed, we

encountered significant barriers to assessing students’ levels

of access for all years because of the limited data the districts

maintained. For example, Coachella’s business practices have been

to mark courses which ended prior to the final term of the school

year as inactive, which made it appear that Coachella failed to

offer courses even though it did actually offer them. Moreover, the

districts we reviewed do not conduct analyses that demonstrate that

they provided all students access to college preparatory coursework.

However, our analysis of available documentation indicates that

access did not significantly hamper students’ ability to complete

required college preparatorycourses.

In addition, all threedistricts we reviewed showed achievement

gaps in completing college preparatory coursework between

certain subgroups of students. Specifically, in SanFrancisco,

underrepresented minorities’ completion rates ranged from

percent to percent, whereas white and Asian students’

completion rates ranged from percent to percent.

Similarly,Stockton’s completion rates for underrepresented

minorities ranged from percent to percent, whereas

completion rates for white and Asian students ranged from

» Even though required by state law, the

California Department of Education

provides only minimal assistance to

districts to ensure students have access

to college preparatory coursework.

» County offices of education could provide

additional oversight, support, and

guidance to districts to ensure they provide

sufficient access to college preparatory

coursework and adequately assist their

students in completing those courses.

3California State Auditor Report 2016-114

February 2017

percent to percent.

1

However, other subgroups of students—

such as students who are eligible to receive free or reduced price

meals at school, English learners, and youth in foster care—

generally fared better in SanFrancisco than Coachella and Stockton.

In particular, SanFrancisco’s completion rate for these students is

threetimes that of similar students in Stockton and twotimes that

of students inCoachella.

Our analysis suggests that students attending school districts that

establish higher student expectations, coupled with relevant tools

and student support, are more likely to meet those expectations.

Although all threedistricts we reviewed have adopted best

practices to support their students during their high school

careers, SanFrancisco in particular employs a variety of tools

that have likely contributed to its high completion rates. In

addition to aligning its graduation coursework requirements with

coursework requirements necessary for admission to UC and

CSU, SanFrancisco devoted significant resources and support

to help its students succeed. is support includes robust credit

recovery options, including options to repeat failed classes

through summer school and after school, for students who do not

meet requirements. SanFrancisco also implemented systematic,

districtwide identification of students who are at risk of not meeting

coursework requirements and then intervenes by meeting with

those students and notifying their parents. Although Stockton and

Coachella offered their own best practices, opportunities remain

for improvement, particularly with regard to identifying and

providing support for students who are struggling to meet college

preparatoryrequirements.

Further, the California Department of Education (Education) and

county offices of education could provide additional oversight,

support, and guidance to districts to ensure they provide sufficient

access to college preparatory coursework and adequately assist

their students in completing those courses. Although each of

the threedistricts we visited stressed the importance of college

preparatory coursework completion, no clear statewide framework

exists for ensuring that districts meet that goal. State law requires the

superintendent of public instruction, who heads Education, to assist

districts to ensure that all public high school students have access

to a core curriculum that meets the admission requirements of UC

and CSU. However, Education currently provides only minimal

assistance to districts: over the last fouryears, the only guidance it

has offered was oneletter.

1

We used the University of California’s (UC) definition for underrepresented minorities. Specifically,

the UC considers underrepresented minorities to be Chicanos/Latinos, African Americans, and

AmericanIndians.

California State Auditor Report 2016-114

February 2017

4

Selected Recommendations

If the Legislature wishes to further prioritize students’ completion

of college preparatory coursework, it should ensure gradenine

students are ready for the rigors of such work by devoting

additional resources or reallocating existing resources for

educational efforts beginning in kindergarten and continuing

through grade eight.

To increase students’ completion rates, districts should take the

followingactions:

• Develop and institute a model similar to SanFrancisco’s

system that will allow them to determine whether students are

completing grade-level college preparatory coursework and to

intervene asnecessary.

• Create a robust and stable network of credit recovery options

that reflect the needs of their student populations. ese

options—which the districts should monitor for effectiveness—

should include summer school courses and eveningcourses.

To comply with existing law and ensure that students receive

sufficient access to college preparatory coursework, Education

should provide additional training and guidance to districts

throughout the State on the creation and application of appropriate

district and school level accessanalyses.

Agency Comments

Education did not agree with our recommendation, but stated it would

continue to provide assistance to districts as required by statelaw.

Stockton stated it is working to improve services to students in

all areas, including access to and successful completion of college

preparatory courses. Coachella stated that it will continue to build

personnel capacity and programs to help foster improvements

in both student achievement and system processes in support of

students. San Francisco did not provide a response to theaudit.

5California State Auditor Report 2016-114

February 2017

Introduction

Background

ere were high school districts and unified school districts—

that include students from kindergarten to grade —in California

with nearly .millionenrolled high school students in the –

school year. To ensure that all of these students have the skills and

knowledge necessary to succeed, districts have been increasing

the emphasis they place on college readiness. According to Higher

Education in California, a report published by the Public Policy

Institute of California (PPIC), the State’s higher education system is

not keeping up with the changing economy. e PPIC projects that

if current trends persist, percent of jobs in will require at

least a bachelor’s degree. However, population and education trends

suggest that only percent of working-age adults in California will

have bachelor’s degrees by—a shortfall of .million college

graduates. e PPIC suggests that the State needs to act now to

close this skills gap and meet futuredemand.

College Preparatory Coursework Requirements

Since the University of California (UC) has required

highschoolsto submit for approval a list of college

preparatory courses that fulfill the requirements for

admission to UC. In the Legislature required of the

California State University (CSU), and requested of UC,

to establish a model set of uniform academic standards

for high school courses for admission to CSU and UC.

As Figure on the following page shows, these academic

standards encompass the high school coursework UC

and CSU require for admission. ese courses are called

the a‑g courses because of the letters assigned to each

subject area: a is for history, b is for English, and so on.

Only courses certified through the UC’s course approval

process are valid for admission purposes to both the UC

and CSU systems. e intent of college preparatory

coursework is to ensure that students attain a body of

general knowledge that will provide breadth and

perspective to new, more advancedstudy.

To qualify as an a-g course, a high school course

must be certified through the UC’s course approval

process, as we further describe in the textbox.

According toUC’s associate director of undergraduate

admissions, UC approves these courses based on the

courses meeting specific criteria. UC maintains lists

Additional Information About the

UC Course Approval Process

• All college preparatory courses must be certified by UC

for students to receive college preparatory credit. Courses

that are approved by UC meet both the UC and the CSU’s

admission requirements. UC is the only state entity that

certifies college preparatory courses. CSU adopted the

same basic college preparatory curriculum and relies on

UC to approve thecourses.

• To certify a course, California high schools and online

schools submit college preparatory courses in the

sevensubject areas to UC forapproval.

• UC evaluates course submissions based on criteria

developed by UC’sfaculty.

• UC maintains lists of college preparatory courses for each

school and instructs schools to update the lists regularly.

The course lists for each school should include all courses

available to students for the upcoming academicyear.

Source: California State Auditor’s review of information from

UCand theCSU.

6 California State Auditor Report 2016-114

February 2017

of each school’s college preparatory courses and instructs schools

to update lists annually. Although other states’ university systems

have general coursework requirements, only California, Georgia,

Nevada, and Kansas have statewide processes in place to centrally

approve those courses required for collegeadmission.

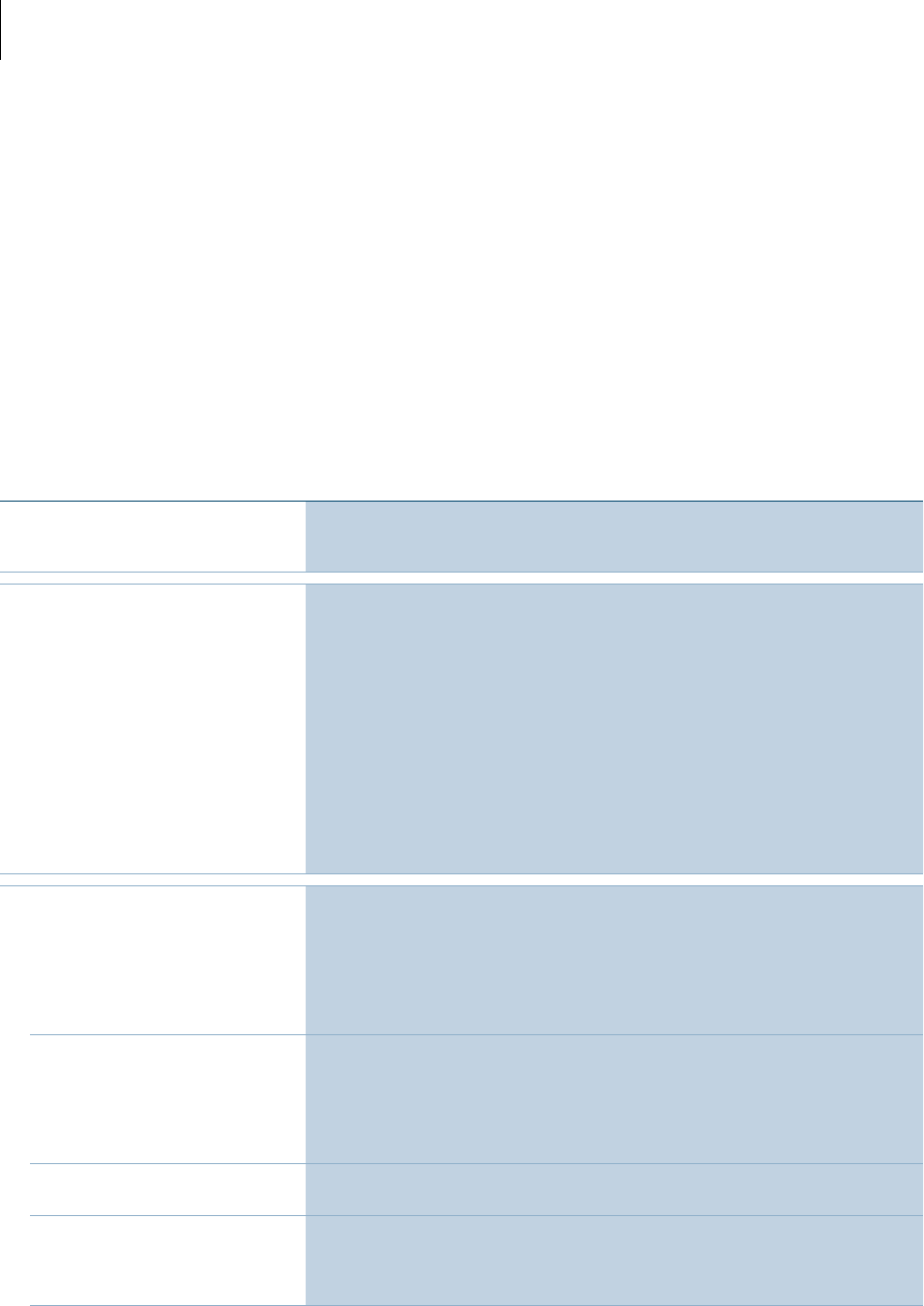

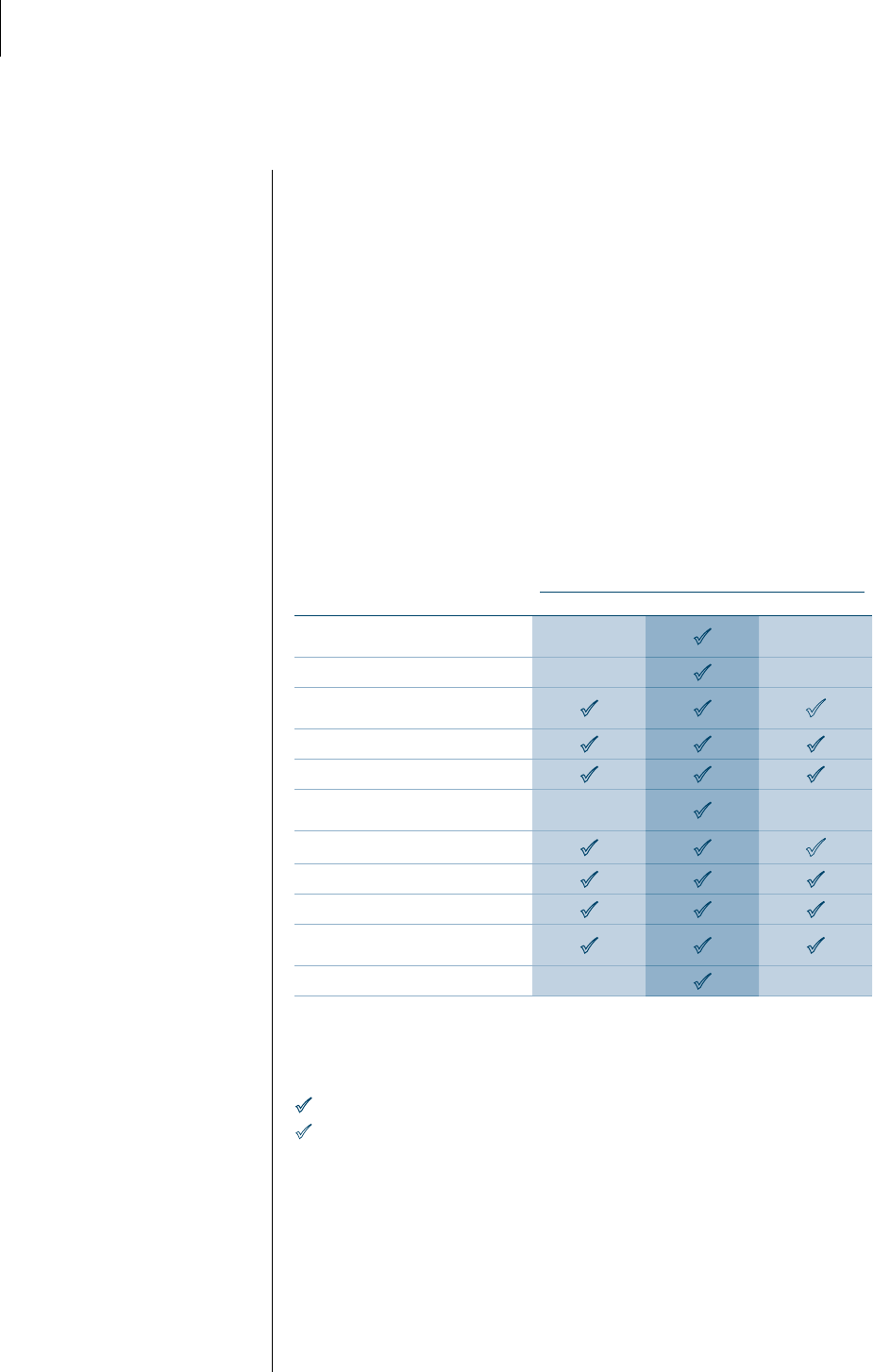

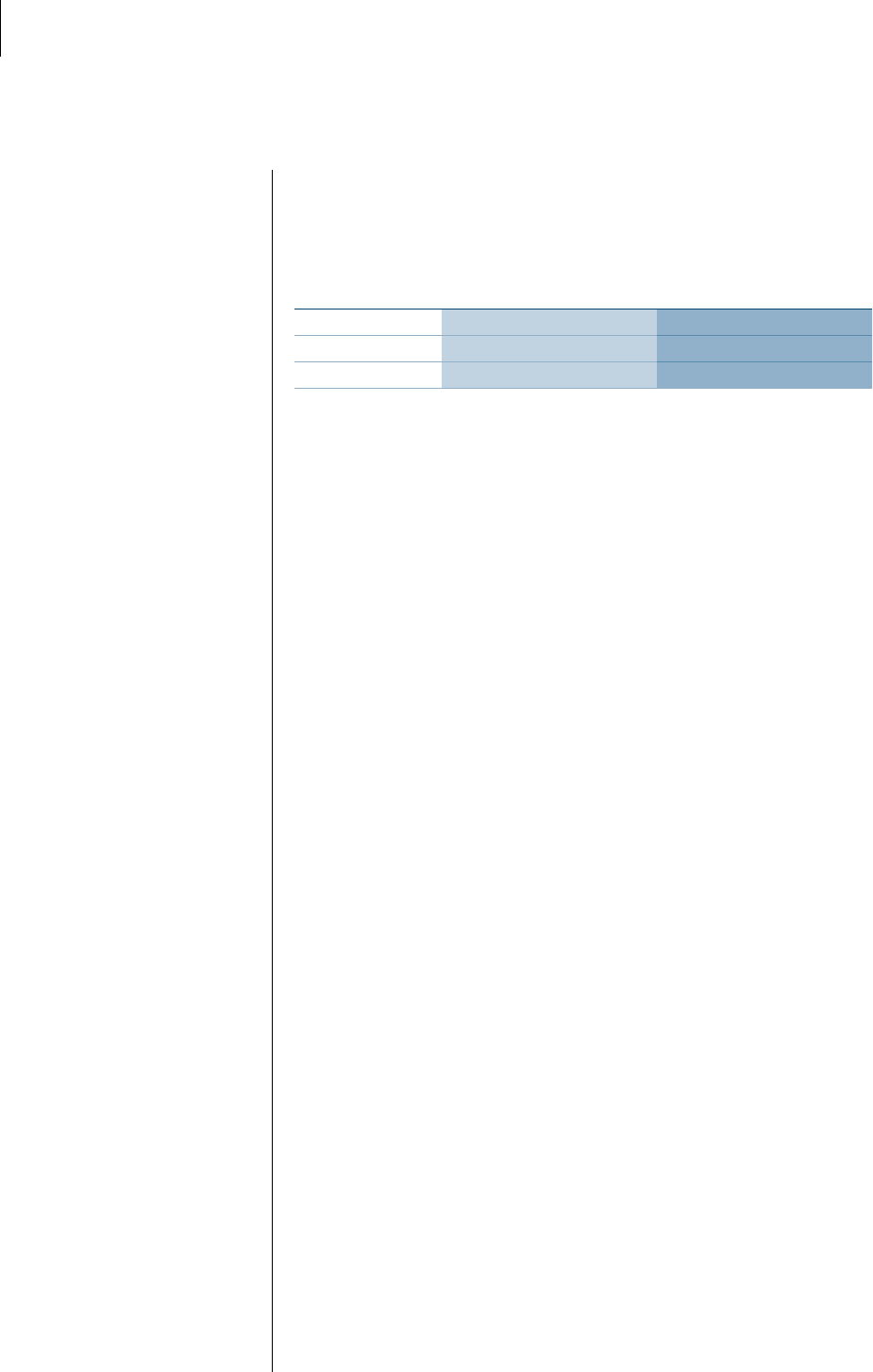

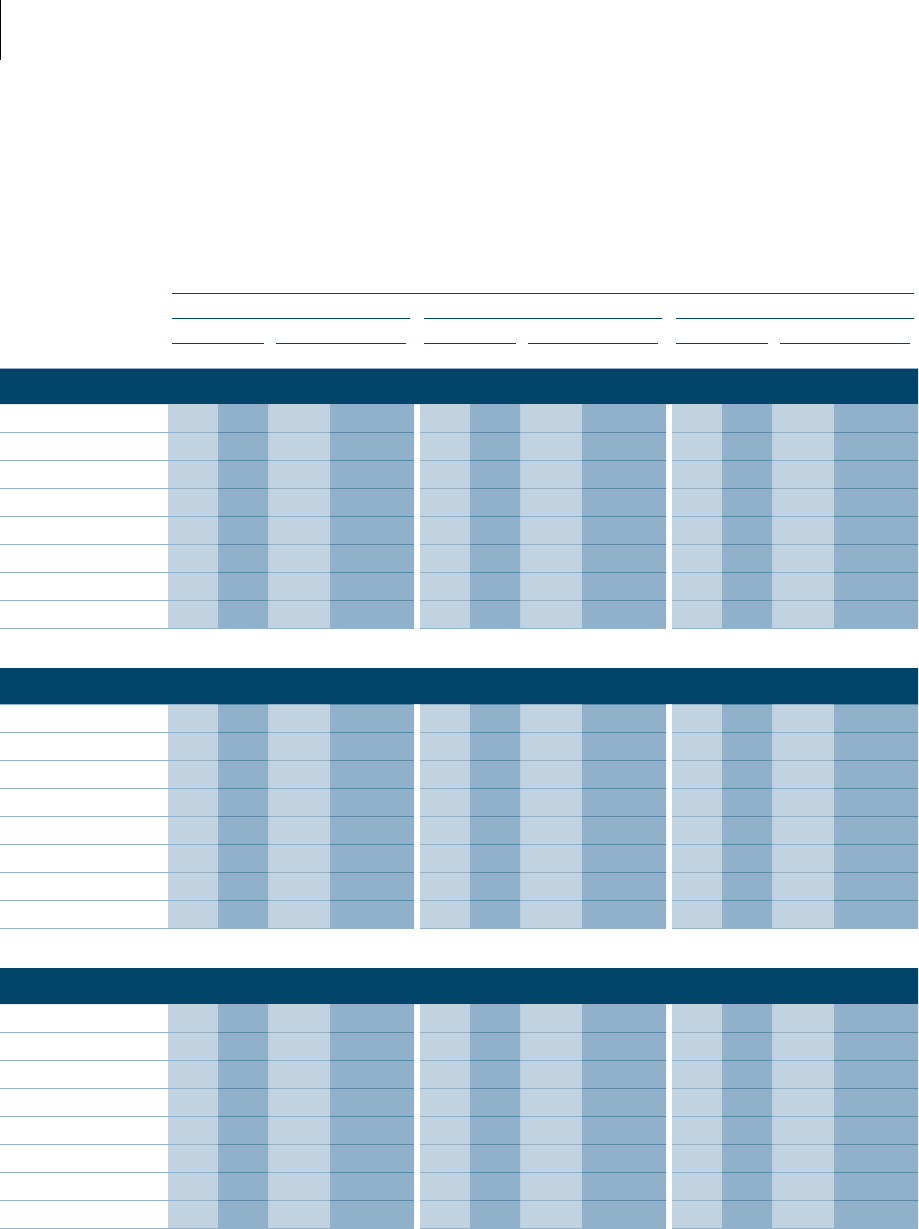

Figure 1

Minimum College Preparatory Coursework Necessary for Admission to California’s PublicUniversities

SUBJECT REQUIREMENTCATEGORY

HISTORY

ENGLISH

MATHEMATICS

LABORATORY SCIENCE

FOREIGN LANGUAGE

VISUAL AND PERFORMING ARTS

COLLEGE PREPARATORY ELECTIVES

g

f

e

d

c

b

a

2

YEARS

4

YEARS

3

YEARS

2

YEARS

2

YEARS

1

YEAR

1

YEAR

Source: The University of California (UC).

Notes: Students must complete each course with a grade of C- or better to be admitted to California’s public universities.

UC refers to Foreign Language as languages other than English.

State law requires districts to provide all qualified students with

timely opportunities to enroll in each college preparatory course

necessary to fulfill the requirements for admission to the State’s

public universities. Although state law sets certain minimum

graduation requirements for high school students throughout

the State, districts can adopt other coursework requirements.

For example, districts may require varying levels of math or

foreign language requirements for students to be eligible to

graduate. Similarly, school districts have the option of requiring all

students to complete college preparatory coursework to graduate.

7California State Auditor Report 2016-114

February 2017

SanFrancisco, SanDiego, and LosAngeles Unified School Districts,

among others, require students to complete a full sequence of

college preparatory courses before they cangraduate.

Educational Funding and Oversight

California’s education system involves both statewide and local

entities. e State Board of Education (State Board) is the State’s

kindergarten through grade policy-making body; it also adopts

academic standards, assessments, and templates for local control

and accountability plans. e California Department of Education

(Education), on the other hand, is responsible for implementing the

policies created by the State Board and overseeing school districts.

Education also receives data from schools about graduation rates,

enrollments, and other statistics through a program known as

the California Longitudinal Pupil Achievement Data System.

In addition, the county offices of education (county offices)

are responsible for examining and approving school district

budgets. County offices may also provide or help formulate

new curricula and instructional materials and training and data

processingservices.

e adoption of the Local Control Funding Formula (funding formula)

in revised the funding allocation for districts. In addition,

under this funding formula, districts receive specific funds to help

unduplicated students. State law describes an unduplicated student as

a pupil who is either classified as an English learner, eligible for free or

reduced price meals, or is a fosteryouth.

Further, the Legislature approved additional funding for districts

in when it created the College Readiness Block Grant

(Block Grant). e Block Grant allocated million to

provide additional support to high school students, particularly

unduplicated students, to increase the number who enroll in

institutions of higher education and complete bachelor’s degrees

within fouryears. Education distributed the funds to districts based

on the number of unduplicated high school students they enrolled

in –. Districts can use the funds for support activities such

as professional development for teachers, administrators, and

counselors; counseling programs; and programs to expand access to

coursework to satisfy the college preparatory courserequirements.

8 California State Auditor Report 2016-114

February 2017

Scope and Methodology

e Joint Legislative Audit Committee (Audit Committee) directedthe

California State Auditor to conduct an audit of college preparatory

coursework at a selection of high schools from threeschool districts.

We list the objectives that the Audit Committee approved and the

methods we used to address those objectives in Table.

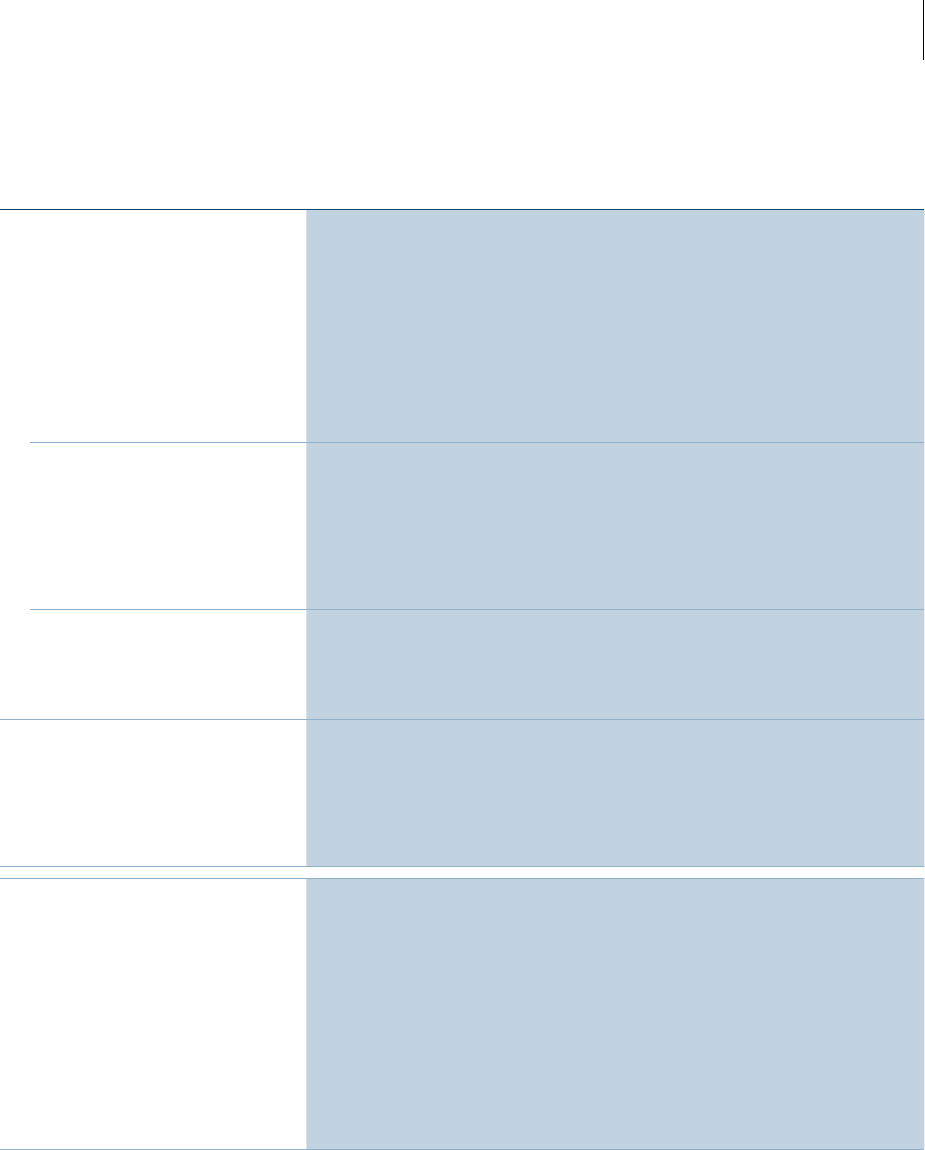

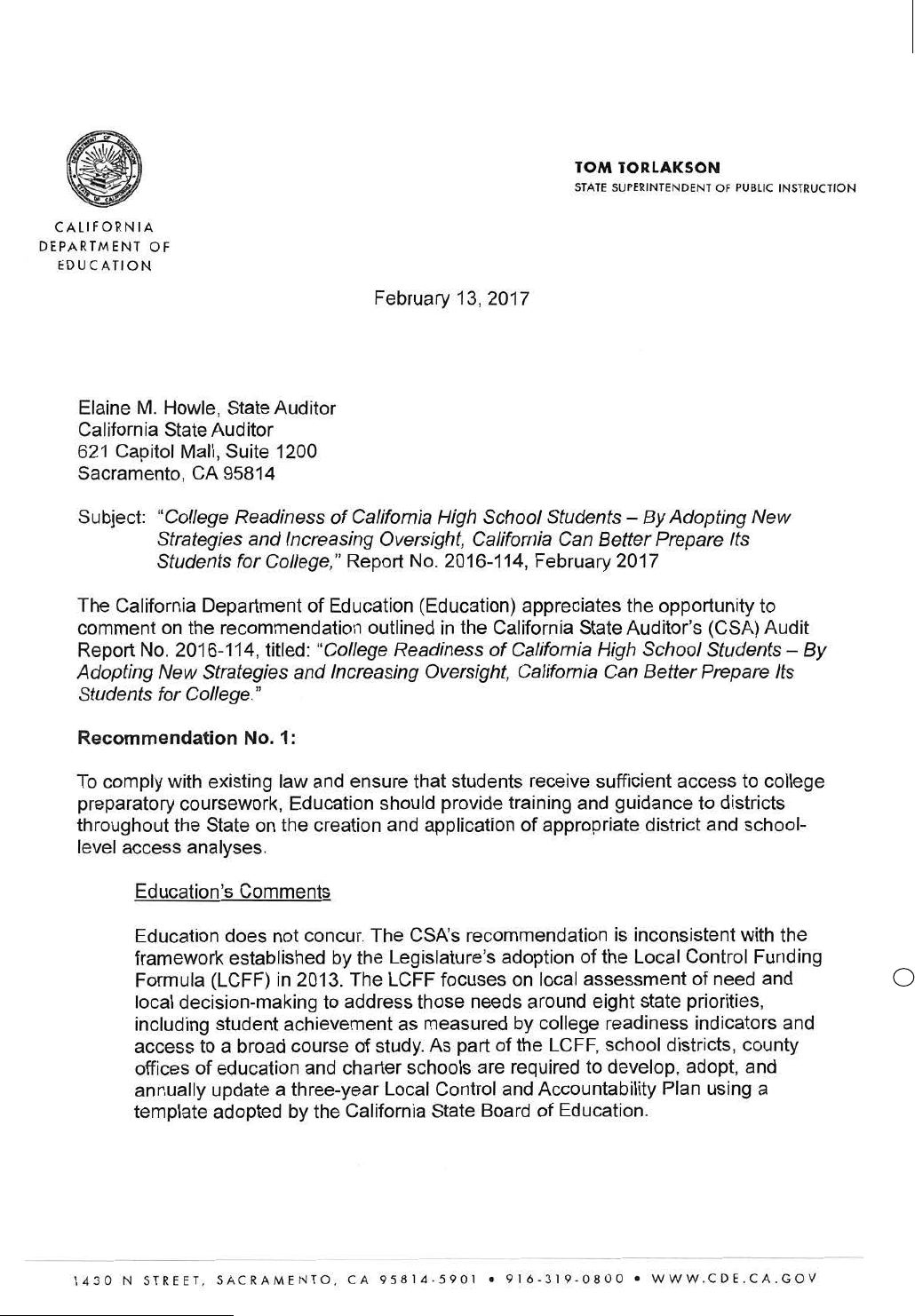

Table 1

Audit Objectives and the Methods Used to Address Them

AUDIT OBJECTIVE METHOD

1 Review and evaluate the laws, rules,

and regulations significant to the

auditobjectives.

Reviewed relevant laws, regulations, and other relevant background materials applicable to access

to and completion of a–gcourses.

2 Determine the percentage of a–gcourses

offered by each district and selected high

school. To the extent possible, determine

how many students at the high schools

are eligible to enroll in these classes

and whether the number of available

courses is sufficient to offer courses to all

eligiblestudents.

• Selected Coachella Valley, SanFrancisco, and Stockton Unified School Districts and sixhigh

schools within those districts from among the 13potential districts noted in the audit request

based on a variety of factors, including a–g completion rate, unduplicated pupil percentage,

and geographiclocation.

• Obtained and analyzed student-level data from our selected districts and high schools for

graduation years2013 through2015 for all enrolled students to determine whether sufficient

access to college preparatory courseworkexisted.

• Reviewed master schedules at each of the sixhighschools.

• Obtained and analyzed certain enrollment and completion data from the California Department

of Education (Education), including the percentage of a–g courses offered and statewide

completionrates.

• All of the districts we interviewed confirmed that there are no eligibility requirements for college

preparatorycoursework.

3 At each district and the selected high

schools, determine the following

information, to the extent possible, and

whether barriers exist that prevent specific

populations of students from enrolling

in or completing a–g coursework at rates

comparable to those of theirpeers:

• Obtained and analyzed student-level enrollment and completion data from our selected districts

and high schools for graduation years2013 through2015.

• Interviewed district and high school personnel related to college preparatory coursework barriers

that students mayface.

a. The total number of students enrolled,

categorized by race, ethnicity,

gender, unduplicated pupil status

(as defined by California Education

Code section42238.02), and English

learnerstatus.

Obtained and analyzed student-level enrollment and completion data from our selected districts and

high schools for graduation years2013 through2015.

b. The percentage of students, by grade,

enrolled in a–g courses.

Obtained and analyzed student-level enrollment and completion data from our selected districts and

high schools for graduation years2013 through2015.

c. Enrollment rates for a–g courses by

course, grade, race, ethnicity, gender,

unduplicated pupil status, and English

learnerstatus.

Obtained and analyzed student-level enrollment and completion data from our selected districts and

high schools for graduation years2013 through2015.

9California State Auditor Report 2016-114

February 2017

AUDIT OBJECTIVE METHOD

d. The percentage of students on track to

complete a–g coursework bygrade.

• Obtained and analyzed student-level enrollment and completion data from our selected

districtsand high schools for graduation years2013 through2015.

• Defined an on track model based on University of California (UC) and California State University(CSU)

credit and course requirements and interviews with district personnel. This model does

not accountfor all of the means by which students can bypass the general a–g coursework

requirements. For example, the UC and CSU allow students to take and pass an Advanced

Placement exam instead of completing a related a–g course. Moreover, there are certain

validation rules for circumstances in which students are presumed to have completed the

lower-level coursework if they have successfully completed advanced work in an area of sequential

knowledge.Our model includes the foreign language validation rule. Finally, our model considers

students to have met the requirements if they received a C- or better in eachcourse.

e. The a–g course completion rate by

course, grade, race, ethnicity, gender,

unduplicated pupil status, and English

learnerstatus.

• Obtained and analyzed student-level enrollment and completion data from our selected

districts and high schools for graduation year2013 through2015.

• Interviewed district and high school personnel related to college preparatory

courseworkcompletion.

• Obtained and analyzed studenttranscripts.

• Identified and verified district, high school, and charter school best practices related to college

preparatory courseworkcompletion.

f. The average grade point average (GPA)

for students completing a–g coursework

by grade, race, ethnicity, gender,

unduplicated pupil status, and English

learnerstatus.

Obtained and analyzed student level enrollment and completion data, including GPAs, from our

selected districts and high schools for graduation years2013 through2015.

4 Review and assess the process that the

districts and high schools use to offer

a–gcoursework tostudents.

• Interviewed district and high school personnel to determine the process used to create the

master schedule each year and to submit a–g courses for approval to theUC.

• Reviewed and assessed the UC’s a–g requirements and its process for reviewing and approving

a–gcourses.

• Compared UC approved a–g courses to courses offered at our selected highschools.

• Determined the level of outreach and interaction the UC has with districts andschools.

5 Review and assess any other issues that are

related to theaudit.

• Interviewed and gathered documents from Education, County Offices of Education,

theCalifornia Collaborative for Education Excellence, the State Board of Education, and the UC to

determine their role, if any, related to college preparatorycoursework.

• Obtained and analyzed the college preparedness portions of the local control and accountability

plans for each of the threedistricts.

• Interviewed personnel in the remaining 10districts noted in the audit request related to college

preparatory coursework access andcompletion.

• Reviewed other states to determine whether similar a–g requirementsexist.

• Obtained a list from the UC of all school districts in the State that did not offer at least onecourse

in each a–g category. We verified that those districts all offer at least one course in each a-g

category, either by correcting past master schedule errors, or by offering online courses that

would satisfy therequirement.

Sources: California State Auditor’s analysis of Joint Legislative Audit Committee audit request number2016-114, planning documents, and analysis of

information and documentation identified in the column titledMethod.

10 California State Auditor Report 2016-114

February 2017

Assessment of Data Reliability

In performing this audit, we obtained electronic data files extracted

from the information systems listed in Table beginning on the

following page. e U.S.Government Accountability Office, whose

standards we are statutorily required to follow, requires us to

assess the sufficiency and appropriateness of computer-processed

information that we use to support findings, conclusions, or

recommendations. Table describes the analyses we conducted

using data from these information systems, our methods for

testing, and the results of our assessments. Although these

determinations may affect the precision of the numbers we present,

there is sufficient evidence in total to support our audit findings,

conclusions, andrecommendations.

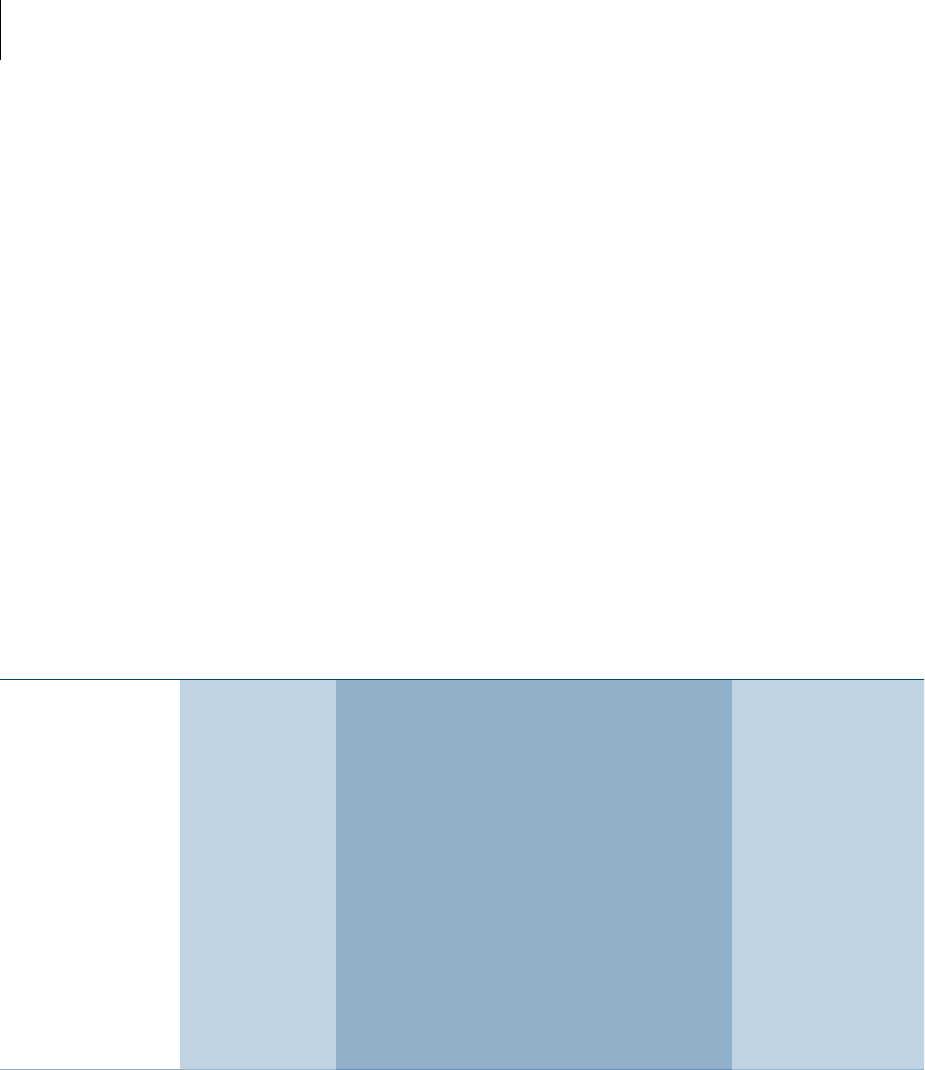

Table 2

Methods Used to Assess Data Reliability

INFORMATION SYSTEM PURPOSE METHOD AND RESULT CONCLUSION

SanFrancisco Unified

School District

(SanFrancisco)

Synergy Student

Information System

(Synergy) for 2013–14

through2014–15

Student Information

System for 2009–10

through 2012–13

Horizon System National

School Lunch Program

data for 2009–10

through 2014–15

Foster Focus System

foster youth data

for 2009–10

through2014–15

To determine a–g

completion rates by

students’ race, ethnicity,

gender, unduplicated

pupil status, and

English learnerstatus.

• We performed data-set verification and electronic testing of

key data elements and did not identify any significant issues.

We did not perform full accuracy and completeness testing

of these data because they come from partially paperless

systems, and thus, hard-copy source documentation was

not consistently available for review. However, to gain some

assurance that SanFrancisco’s data contained information

for students applicable to our analysis, we reconciled

the total number of students included in SanFrancisco’s

data for each academic year to the enrollment data the

California Department of Education (Education) publishes on

itswebsite.

• To gain some assurance that SanFrancisco correctly

identified college preparatory coursework, we compared

a selection of course data to the University of California’s

(UC) listing of certified courses and found that SanFrancisco

had misidentified 10courses. However, these courses did

not ultimately affect any students’ overall completion of

a–grequirements.

Undetermined reliability

for thispurpose.

Although this determination

may affect the precision of

the numbers we present,

there is sufficient evidence

in total to support our

findings, conclusions,

andrecommendations.

11California State Auditor Report 2016-114

February 2017

INFORMATION SYSTEM PURPOSE METHOD AND RESULT CONCLUSION

Stockton Unified

SchoolDistrict

(Stockton)

Synergy for 2009–10

through2014–15

eOfficeSuite National

School Lunch Program

data for 2009–10

through2012–13

Coachella Valley

Unified School District

(Coachella)

Aeries Student

Information System

for 2009–10

through2014–15

To determine a–g

completion rates by

students’ race, ethnicity,

gender, unduplicated

pupil status, and

English learnerstatus.

• We performed data-set verification and electronic testing of

key data elements and did not identify any significant issues.

We did not perform full accuracy and completeness testing

of these data because they come from partially paperless

systems, and thus, hard-copy source documentation was

not consistently available for review. However, to gain some

assurance that the districts’ data contained information for

students applicable to our analysis, we reconciled the total

number of students included in each district’s data for each

academic year to the enrollment data Education publishes

on itswebsite.

• To gain some assurance that the districts correctly identified

college preparatory coursework, we compared a selection

of course data to UC's listing of certified courses and

found Stockton and Coachella had misidentified a total of

60courses and 13courses, respectively. These errors resulted

in 171students appearing to meet a–g requirements when

they may not have actually met therequirements.

• We also identified limitations related to the data.

Specifically, we were unable to identify students who

attended Stockton as freshmen in 2009–10, but did not

enroll with the district in subsequent years. This is because

Stockton was still exclusively using its legacy system

for2009–10. When Stockton transitioned from the legacy

system to Synergy, it only copied data for 2009–10 over to

Synergy if the student was still enrolled with the district at

the time of the transition toSynergy.

• Further, Coachella acknowledged that its data for students’

free or reduced price meal status is incomplete. Free or

reduced price meal status is onecomponent used to

identify a student’s unduplicated pupil status. However,

using Coachella’s available free or reduced price meal

data combined with other data, we were still able to

identify 92percent or more of students in each of the

threeCoachella cohorts as having unduplicated pupilstatus.

Not sufficiently reliable

for thispurpose.

Although this determination

may affect the precision of

the numbers we present,

there is sufficient evidence

in total to support our

findings, conclusions,

andrecommendations

SanFrancisco

Synergy for 2013–14

through2014–15

Stockton

Synergy for 2011–12

through2014–15

To determine if there

was sufficient college

preparatory-level

coursework offered

forstudents.

• We performed data-set verification and electronic testing of

key data elements and did not identify any significant issues.

We did not perform accuracy and completeness testing

of these data because they come from partially paperless

systems, and thus, hard-copy source documentation was

not consistently available for review. However, to gain some

assurance that the course data included all courses actually

offered by the districts, we compared 60courses from

student transcripts to the data and did not identify anyissues.

• As discussed previously, Stockton misidentified courses as

college preparatory coursework certified, even though UC

had not certified them. However, we were able to correct for

these errors in this analysis using supplemental information

fromUC.

Undetermined reliability

for thispurpose.

Although this determination

may affect the precision of

the numbers we present,

there is sufficient evidence

in total to support our

findings, conclusions,

andrecommendations.

Education

California Longitudinal

Pupil Achievement Data

System for2014–15

To determine

thepercent of high

school classes at each

district that satisfies an

a–grequirement.

We performed data-set verification and electronic testing of

key data elements and did not identify any significant issues.

We did not perform accuracy and completeness testing of

these data because they are submitted by local educational

agencies and any supporting documentation is maintained

throughout the State. We reconciled the total number of classes

and students included in the data to the numbers Education

reported through its website to gain some assurance that

Education provided all of its relevantdata.

Undetermined reliability

for thispurpose.

Although this determination

may affect the precision of

the numbers we present,

there is sufficient evidence

in total to support our

findings, conclusions,

andrecommendations.

Sources: California State Auditor’s analysis of various documents, interviews, and data from Education, Coachella, SanFrancisco, and Stockton.

12 California State Auditor Report 2016-114

February 2017

Blank page inserted for reproduction purposes only.

13California State Auditor Report 2016-114

February 2017

Chapter 1

SCHOOL DISTRICTS MAY BE ABLE TO SIGNIFICANTLY

IMPROVE STUDENTS’ COLLEGE READINESS BY OFFERING

A RANGE OF ACADEMICSUPPORTS

Chapter Summary

Our review suggests that when school districts (districts) prioritize

college preparatory coursework and the support they provide to

students, they significantly affect the likelihood that students will

graduate from high school having taken the coursework necessary

for admission into the State’s public university systems. In

the SanFrancisco Unified School District (SanFrancisco) aligned

its graduation coursework requirements with the minimum

coursework requirements necessary for admission to the University

of California (UC) and California State University (CSU) systems,

effectively requiring all its students to complete college preparatory

coursework to graduate.

2

Of the threedistricts we reviewed—

SanFrancisco, Stockton Unified School District (Stockton), and

Coachella Valley Unified School District (Coachella)—we found

that SanFrancisco’s college preparatory coursework completion

rates (completion rates) were significantly higher than those of the

other two districts. Specifically, in only percent of Stockton’s

students successfully completed the college preparatory coursework,

while percent of Coachella’s students met these requirements. In

contrast, percent of students in SanFrancisco completed college

preparatorycoursework.

Completion rates at the threedistricts we reviewed were also

heavily influenced by students’ ability to complete coursework on a

prescribed track beginning in grade nine. We found that the majority

of students who fell off track at some point during their high school

careers did so during gradenine. Although few of these students

in any of the threedistricts went on to complete the remainder of

their college preparatory coursework, we found that SanFrancisco

provided a number of resources that ensured that significantly

more of its students met the necessary requirements. Similarly,

underrepresented minorities and English learners in all threedistricts

showed achievement gaps in completing college preparatory

coursework but fared better in SanFrancisco than in the other

districts we reviewed—another likely result of the amount of support

SanFrancisco provides.

2

Although SanFrancisco students must complete the full sequence of college preparatory

coursework, they only need to receive a grade of D or better in these classes to graduate.

However, to be eligible for admission to the State’s public university systems, students must

receive a grade of C- or better in theseclasses.

California State Auditor Report 2016-114

February 2017

14

Completion Rates of College Preparatory Coursework Vary Widely by

School District but Can Be Improved With Increased Expectations and

AppropriateInterventions

School districts statewide, and the three school districts we selected

for review, varied widely in the rates at which their students completed

college preparatory coursework. However, the data show that school

districts, such as SanFrancisco, can increase completion rates when

they increase expectations and corresponding interventions and

support. According to data maintained by the California Department

of Education (Education), completion rates for districts within

the State ranged from percent to percent in –, with

percent of students completing college preparatory coursework

requirement statewide. Education’s data also indicated that Stockton’s

and Coachella’s completion rates were percent and percent,

respectively, in–. In contrast, Education’s data indicated that

SanFrancisco’s completion rate was percent—the second-highest

averagestatewide.

Using a different methodology, which yielded similar results,

we conducted a detailed analysis of student-level cohort data to

determine the completion rates for students who were enrolled in

gradenine in each of the districts we reviewed.

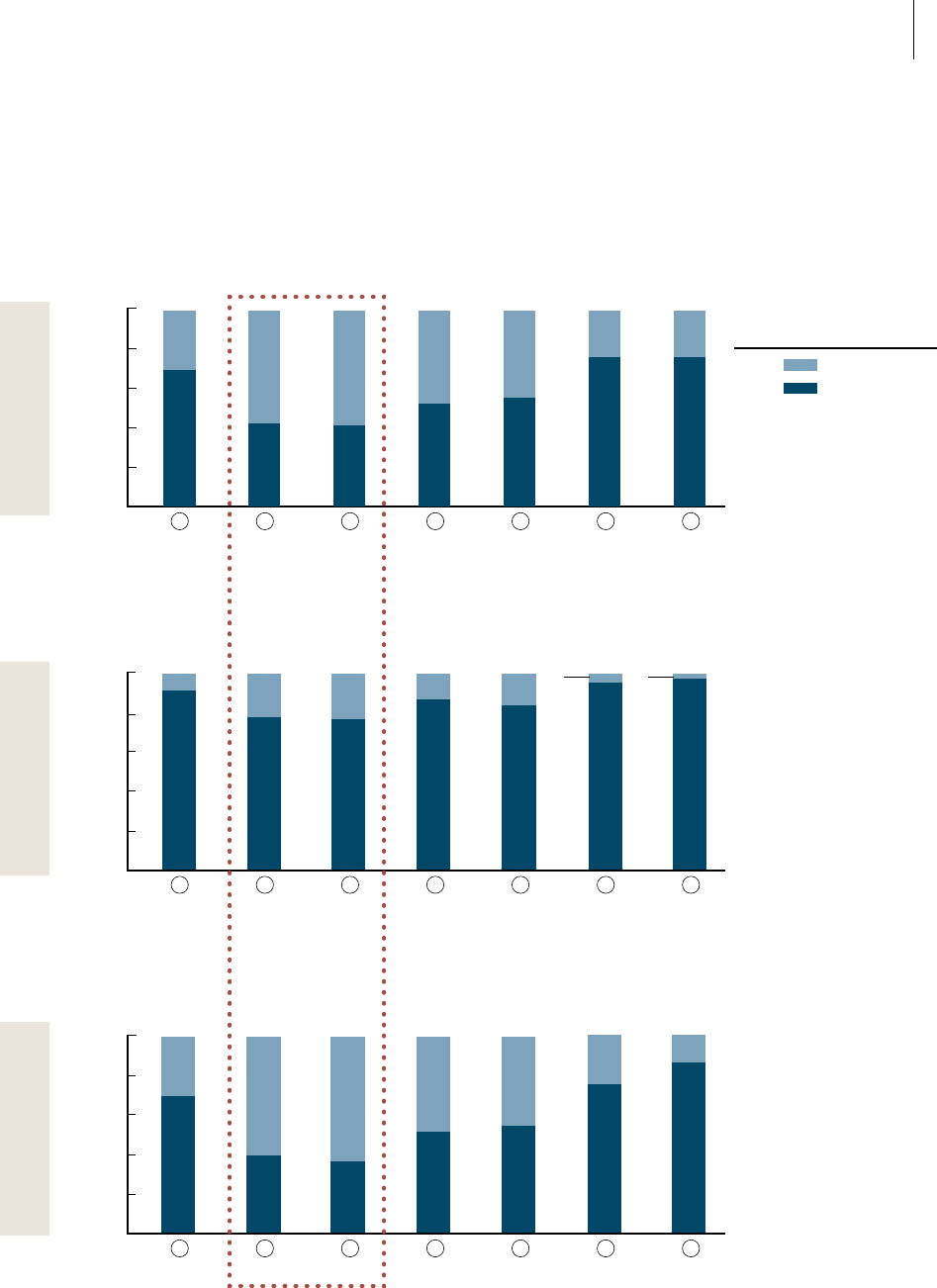

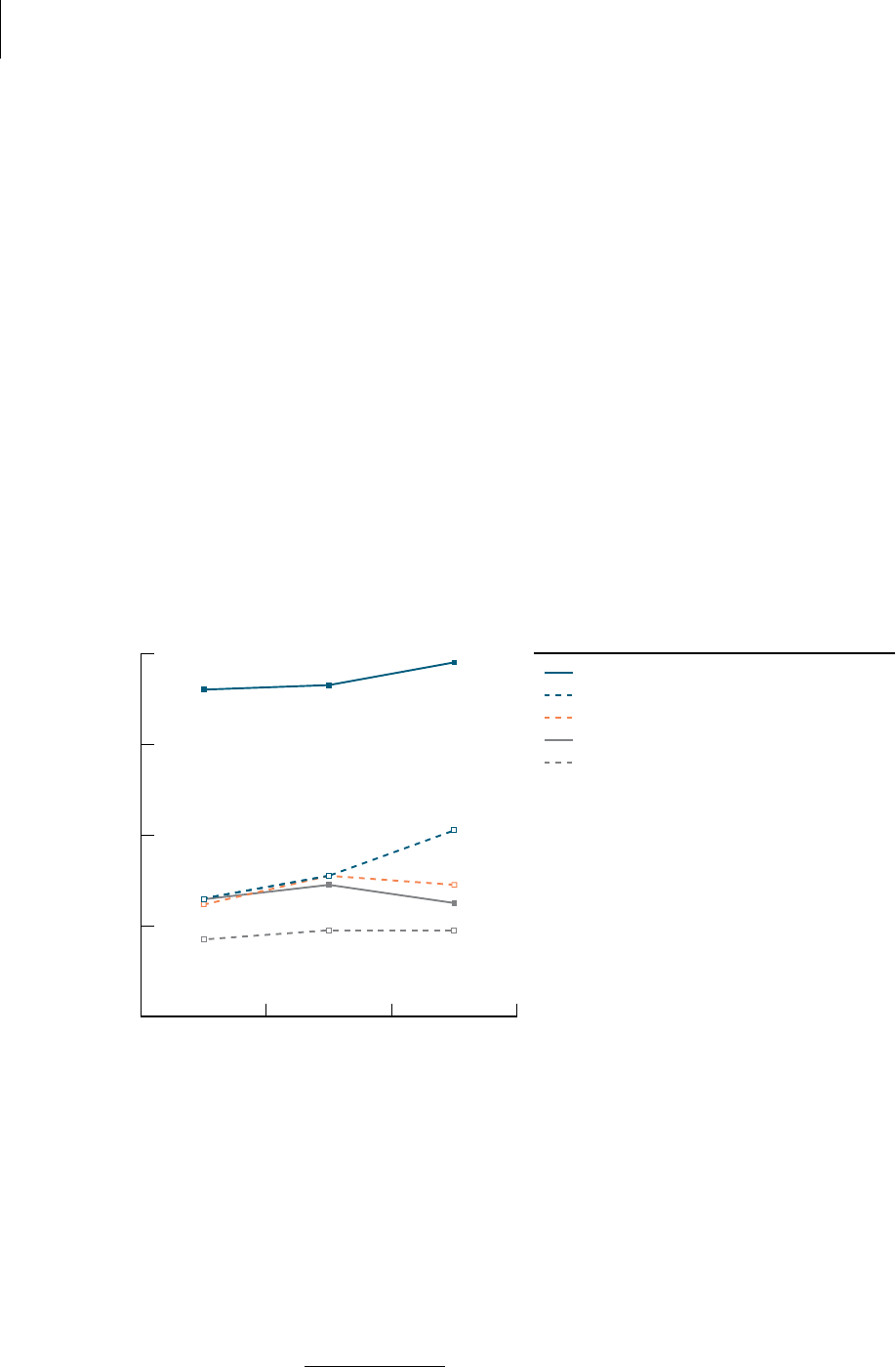

3

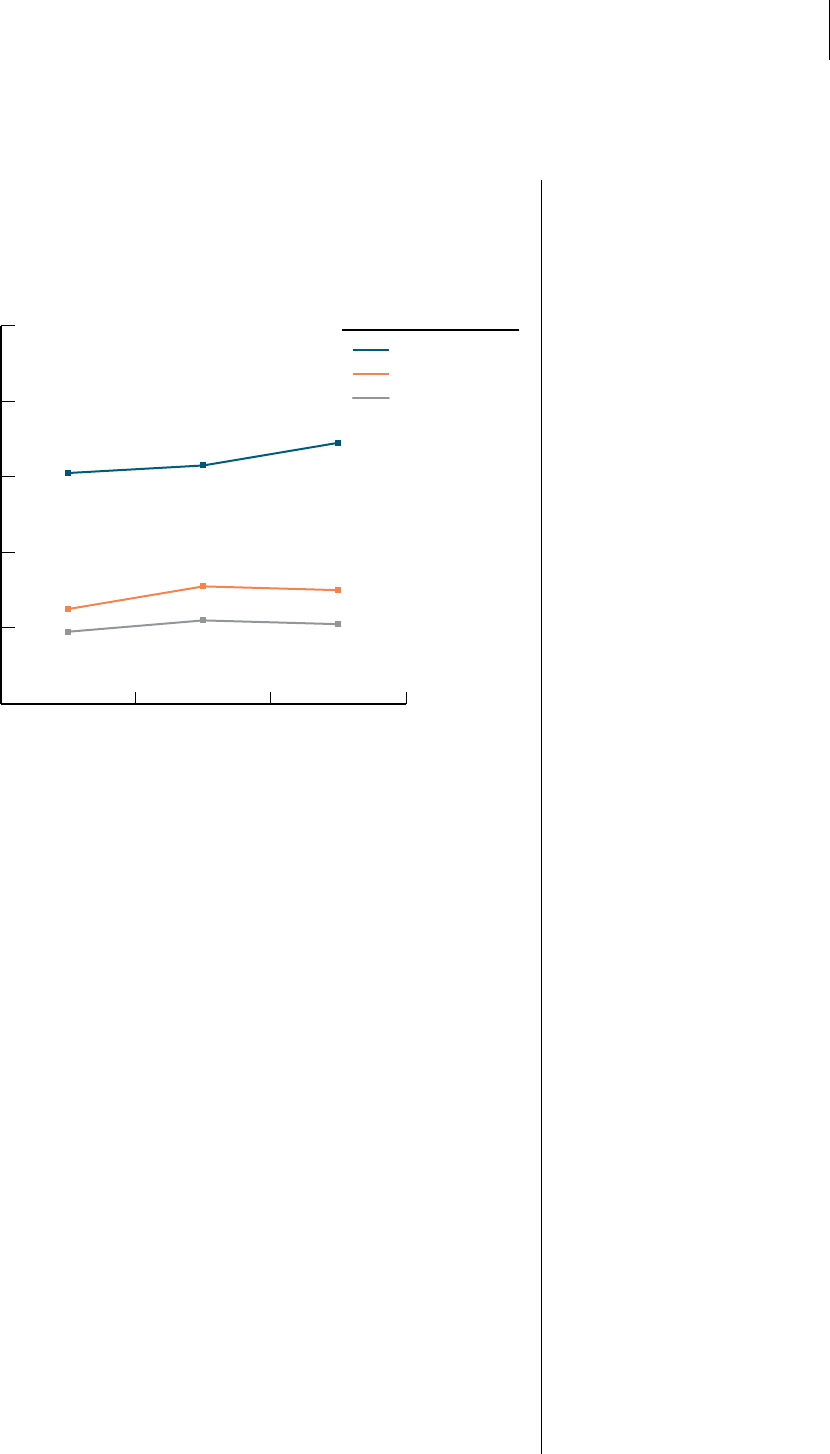

As Figure illustrates,

the completion rates for students in the through graduating

classes ranged from percent to percent in Stockton, percent to

percent in Coachella, and percent to percent in SanFrancisco.

Students’ ability to stay on a prescribed track is critical to their

completing college preparatory coursework. For students to complete

college preparatory coursework necessary for admission into UC or

CSU by the end of grade, they must enroll in and complete—with

a grade of C- or better—courses across several subjects, as we

show in Figure on page.

4

We considered students who enrolled

in and completed the minimum number of courses with a grade of

C- or better each year in the prescribed sequence to be on track.

Students must complete multiple courses for many of these subjects.

For example, students must take fouryears of English; thus, most

students who wish to meet the State’s public university systems’

admission standards will need to complete a college preparatory

English course during each of their four high schoolyears.

3

Each cohort is composed of students who were enrolled in the ninth grade in a given district

for the first time in –, took a class for credit at a high school within the respective

audited district, and received a valid mark. Subsequent cohorts reflected a similar methodology

for– and–. Students remained in the cohort until they left thedistrict.

4

UC and CSU require applicants to receive a C or better in all college preparatory courses to be

eligible for admission. Because UC and CSU do not calculate minuses or pluses (such as a C- or

C+), a student who receives a C- would still be eligible foradmission.

Students’ ability to stay on

a prescribed track is critical

to their completing college

preparatorycoursework.

15California State Auditor Report 2016-114

February 2017

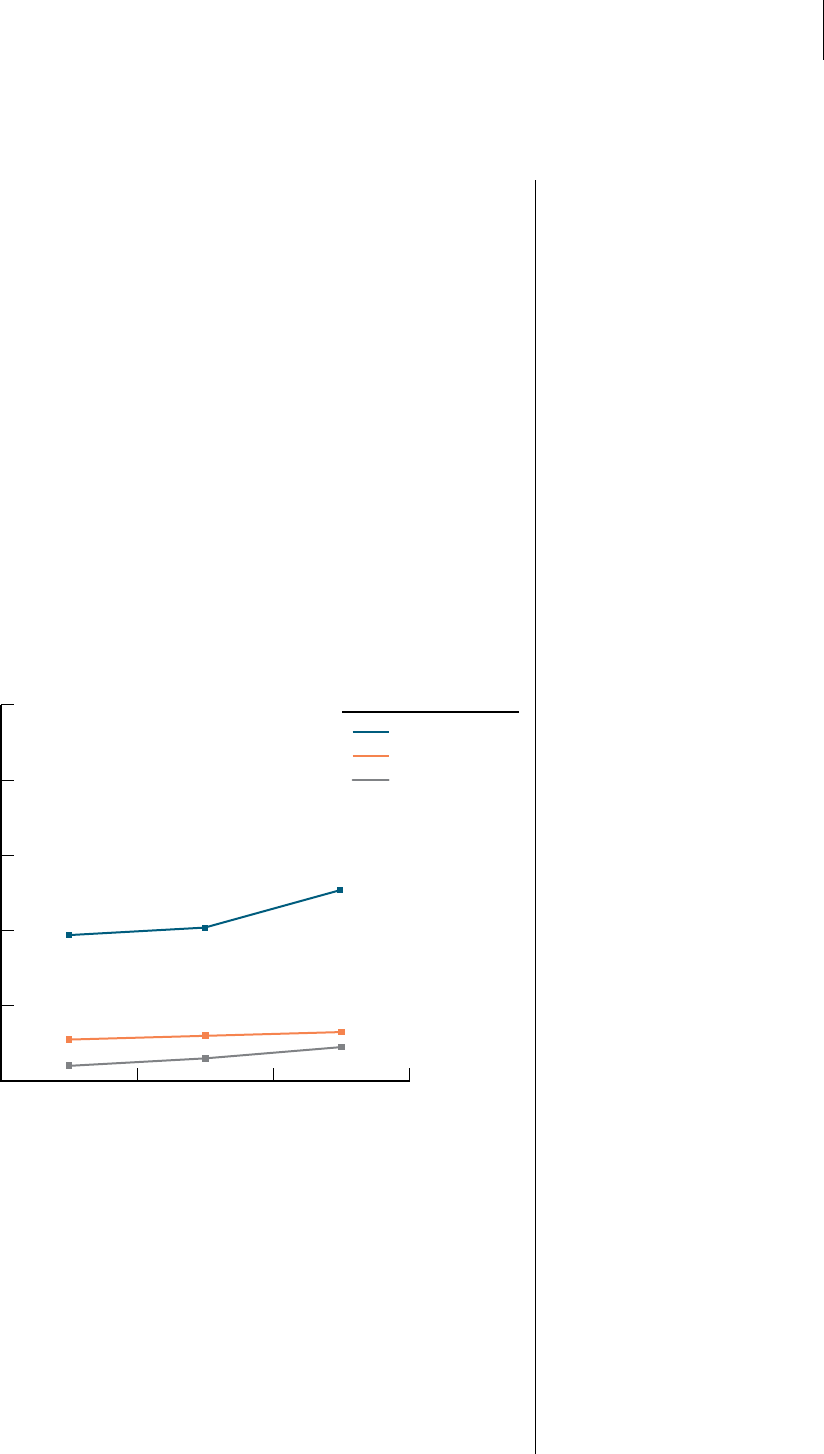

Figure 2

College Preparatory Coursework Completion Rates Vary Significantly in the

ThreeDistricts WeReviewed

Graduation Years 2013 Through 2015

Graduation Year

201520142013

College Preparatory Coursework

Completion Rate

0

20

40

60

80

100%

61%

63%

69%

25%

31%

30%

19%

22%

21%

San Francisco

Coachella Valley

Stockton

UNIFIED SCHOOL DISTRICT

Source: California State Auditor’s analysis of student data provided by CoachellaValley, SanFrancisco,

and Stockton Unified SchoolDistricts.

Note: We excluded students who left thedistrict.

As Table on page shows, the majority of students in graduation

years through in Coachella and Stockton fell off track

at some point during their high school careers and few of those

students went on to complete all the necessary college preparatory

coursework by the end of high school. Specifically, percent and

percent of Coachella and Stockton students, respectively, fell off

track at some point during their fouryears of high school, and only

percent and percent of those students were able to eventually get

back on track and meet all coursework requirements. SanFrancisco

was more successful at keeping students on the prescribed track:

percent fell off track at some point during their high school

careers and the district helped a higher percentage—percent—of

off-track students to eventually complete all the college preparatory

coursework requirements. ese data suggest that districts should

focus resources, when limited, on keeping students on track and,

in particular, on helping students successfully complete gradenine

requiredcoursework.

16 California State Auditor Report 2016-114

February 2017

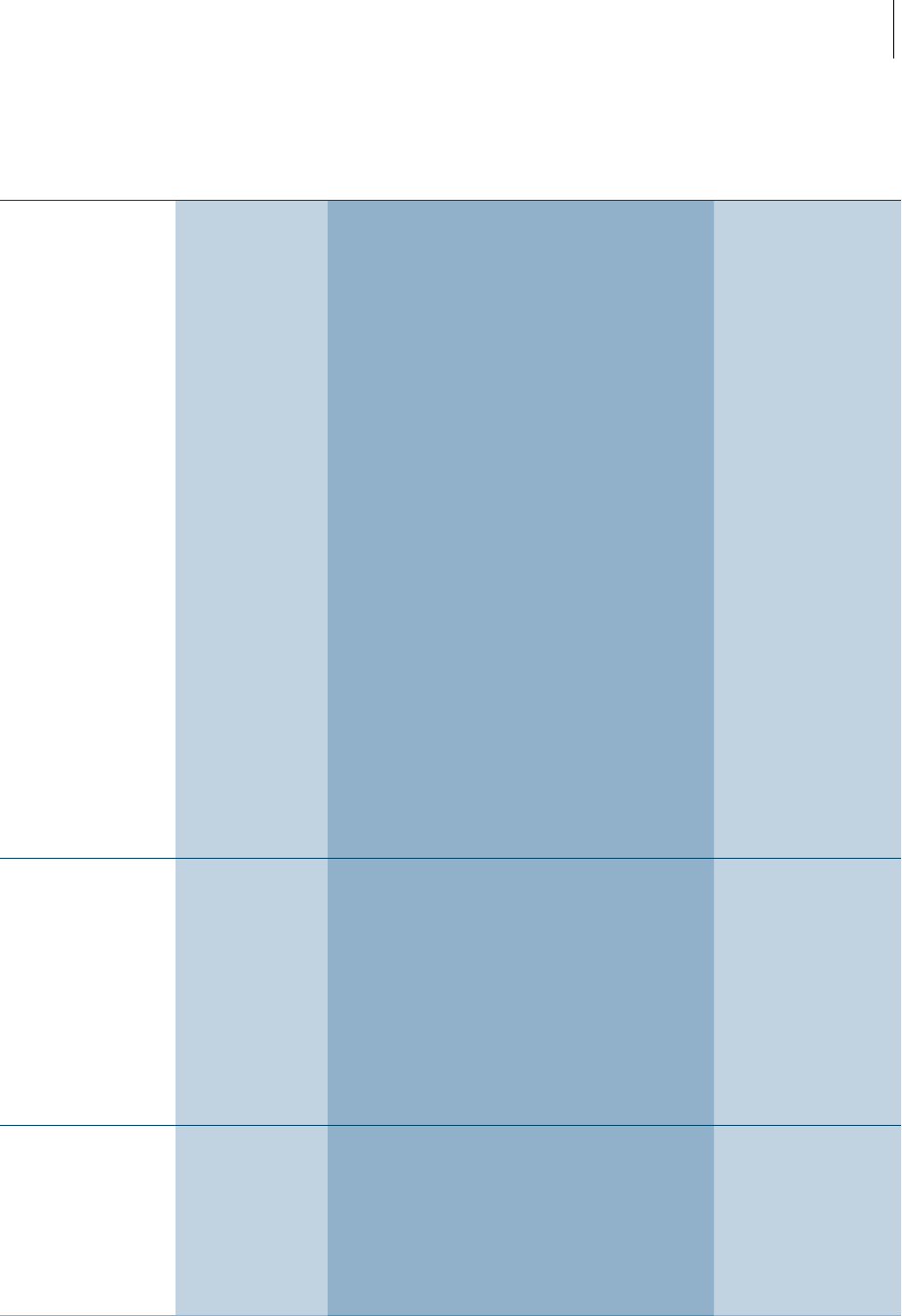

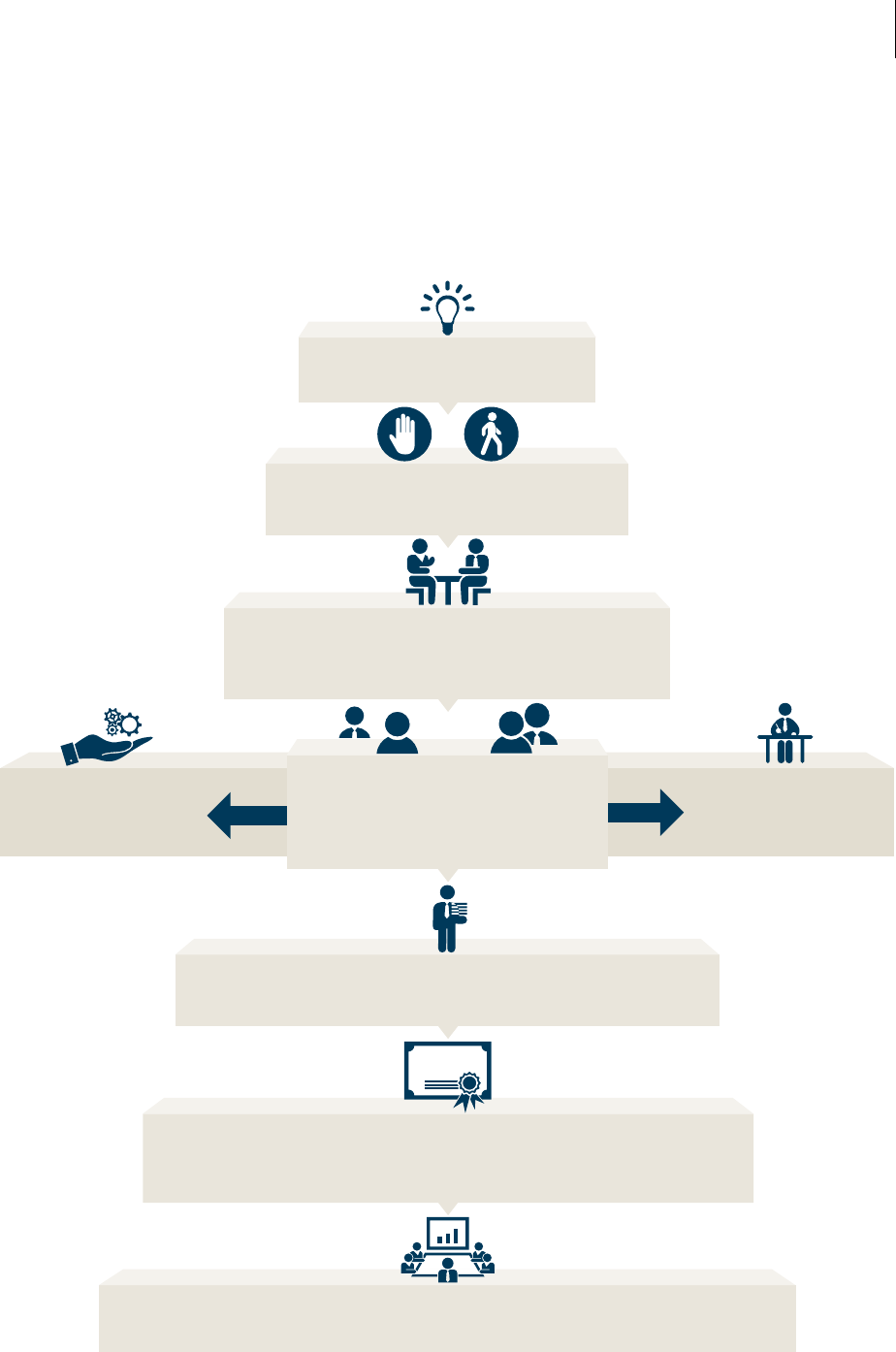

Figure 3

Students Must Complete a General Sequence of Courses to Be On Track to Complete College Preparatory

Requirements by the End of Their Fourth Year

40

credits

English 4 (b)

Spanish 2 (e)

Chemistry (d)

Psychology (g)

12

th

Grade

40

credits

English 3 (b)

Algebra 2 (c)

Spanish 1 (e)

US History (a)

11

th

Grade

40

credits

English 2 (b)

Geometry (c)

World History (a)

Ceramics (f)

10

th

Grade

30

credits

English 1 (b)

Algebra 1 (c)

Biology (d)

9

th

Grade

EXAMPLE OF THE

COLLEGE PREPARATORY PORTION OF A

COURSE SCHEDULE FOR A STUDENT WHO

COMPLETES MINIMUM REQUIREMENTS

4 English (b) 2 Foreign Language

†

3 Math (c) 1 Visual and Performing Arts

2 History (a) 1 College Preparatory Elective

2 Lab Science (d)

Year 4

150 cumulative credits

3 English (b) 1 History

2 Math (c) 1 Lab Science

3 Any a–g* 1 Foreign Language

Year 3

110 cumulative credits

2 English (b)

1 Math (c)

4 Any a–g*

Year 2

70 cumulative credits

1 English (b)

2 Any a–g*

Year 1

30 credits

MINIMUM COLLEGE PREPARATORY

COURSEWORK REQUIREMENTS

TO BE CONSIDERED ON TRACK

15

courses

150

credits

Source: California State Auditor’s analysis of policies provided by CoachellaValley, SanFrancisco, and StocktonUnified School Districts, and the

University ofCalifornia (UC).

Notes: Students must pass all courses with a grade of C- orbetter.

Credits for courses attended during summer school count toward the prior schoolyear.

* a–g = History (a), English (b), Math (c), Science (d), Foreign Language (e), Visual and Performing Arts (f), College Preparatory Elective (g).

†

Although students must complete two years of foreign language courses, validation rules can be applied to meet these requirements by

successfully completing the second semester of a level2 or higher foreign languagecourse. This could reduce the number ofcumulative

creditsrequired.

17California State Auditor Report 2016-114

February 2017

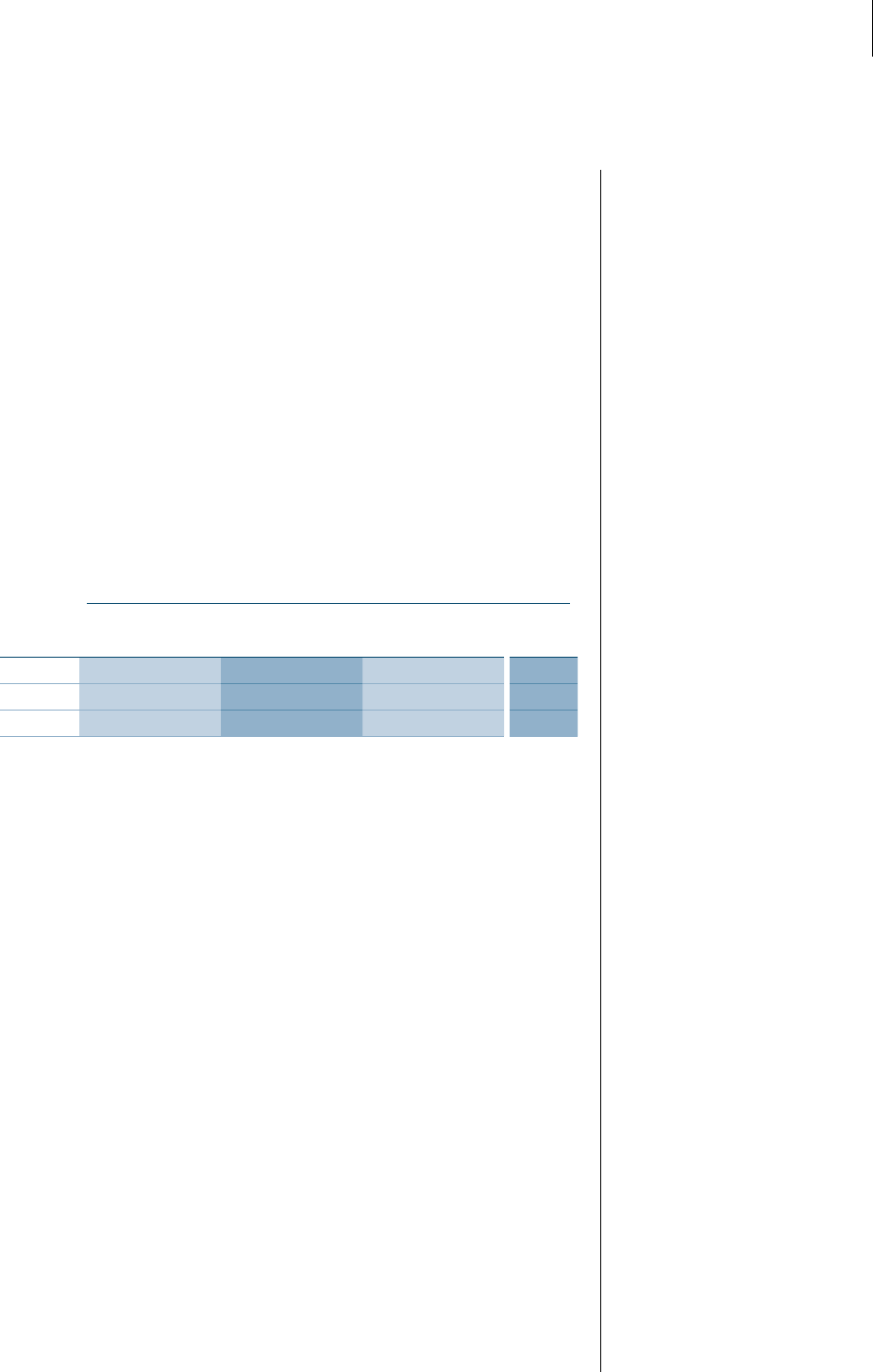

Table 3

Students Who Fell Off Track at Any Point During High School Were Not Likely to Complete College

PreparatoryRequirements

Graduation Years 2013 Through2015

RESULTS OF THE STUDENTS WHO FELL OFF TRACK

UNIFIED

SCHOOL DISTRICT

TOTAL NUMBER OF

STUDENTS WHO

FELL OFF TRACK

PERCENTAGE OF

TOTAL STUDENT

POPULATION WHO

FELL OFF TRACK

MET REQUIREMENTS

BY THE END OF HIGHSCHOOL

DID NOT MEET REQUIREMENTS

BY THE END OF HIGHSCHOOL

NUMBER PERCENTAGE NUMBER PERCENTAGE

Coachella Valley 2,459 79% 245 10% 2,214 90%

SanFrancisco 3,706 41 482 13 3,224 87

Stockton 3,904 84 212 5 3,692 95

Source: California State Auditor’s analysis of data provided by Coachella Valley, SanFrancisco, and Stockton Unified SchoolDistricts.

Note: We excluded students who left thedistrict.

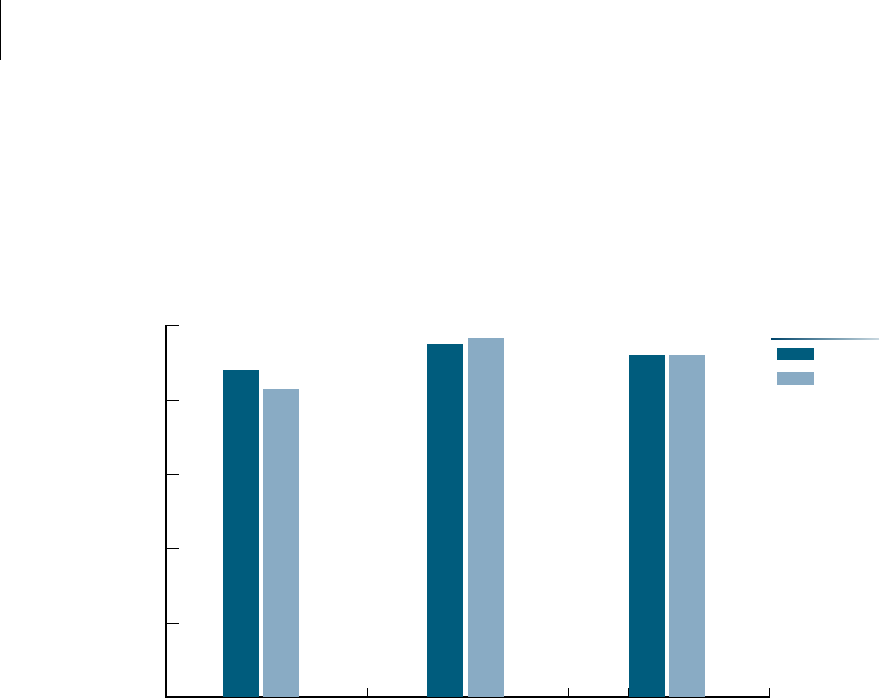

Students Who Fail to Meet College Preparatory Requirements

as Freshman Are Unlikely to Complete Coursework Needed for

Admission to the State’s Public UniversitySystems

Completion rates at the threedistricts we reviewed depended

heavily on students’ ability to complete coursework on a prescribed

track beginning in gradenine. At each of the threedistricts,

we found that the majority of students who fell off this track

did so during gradenine and few of them went on to complete

the remainder of their college preparatory coursework. us, it

is imperative that districts ensure students’ enrollment in and

successful completion of college preparatory coursework beginning

in their firstyear of highschool.

Seventy-twopercent of students who fell off track in Stockton,

percent of those who did so in Coachella, and percent

of those who fell of track in SanFrancisco, fell off track during

gradenine, as Figure on the following pageshows. Of concern

is that an average of only percent of the students who fell off

track in gradenine in the threedistricts we reviewed completed

the coursework necessary to gain admission to the State’s

public university systems, which highlights the importance of

that firstyear of high school. Moreover, as Figure on page

shows, students in SanFrancisco who fell off track in gradenine

had slightly better success—percent—in completing college

preparatory coursework than comparable students in Coachella

and Stockton—at percent and percent, respectively. Falling off

track during gradenine likely presents the greatest challenge for

students because getting back on track requires them to successfully

complete an even more demanding course load than their peers

18 California State Auditor Report 2016-114

February 2017

who did not fall off track. For example, if a ninth-grade student

receives an F in English, that student would need to receive a C-or

better in both English and in a subsequent year, in addition to

passing their other necessary classes, to get back ontrack.

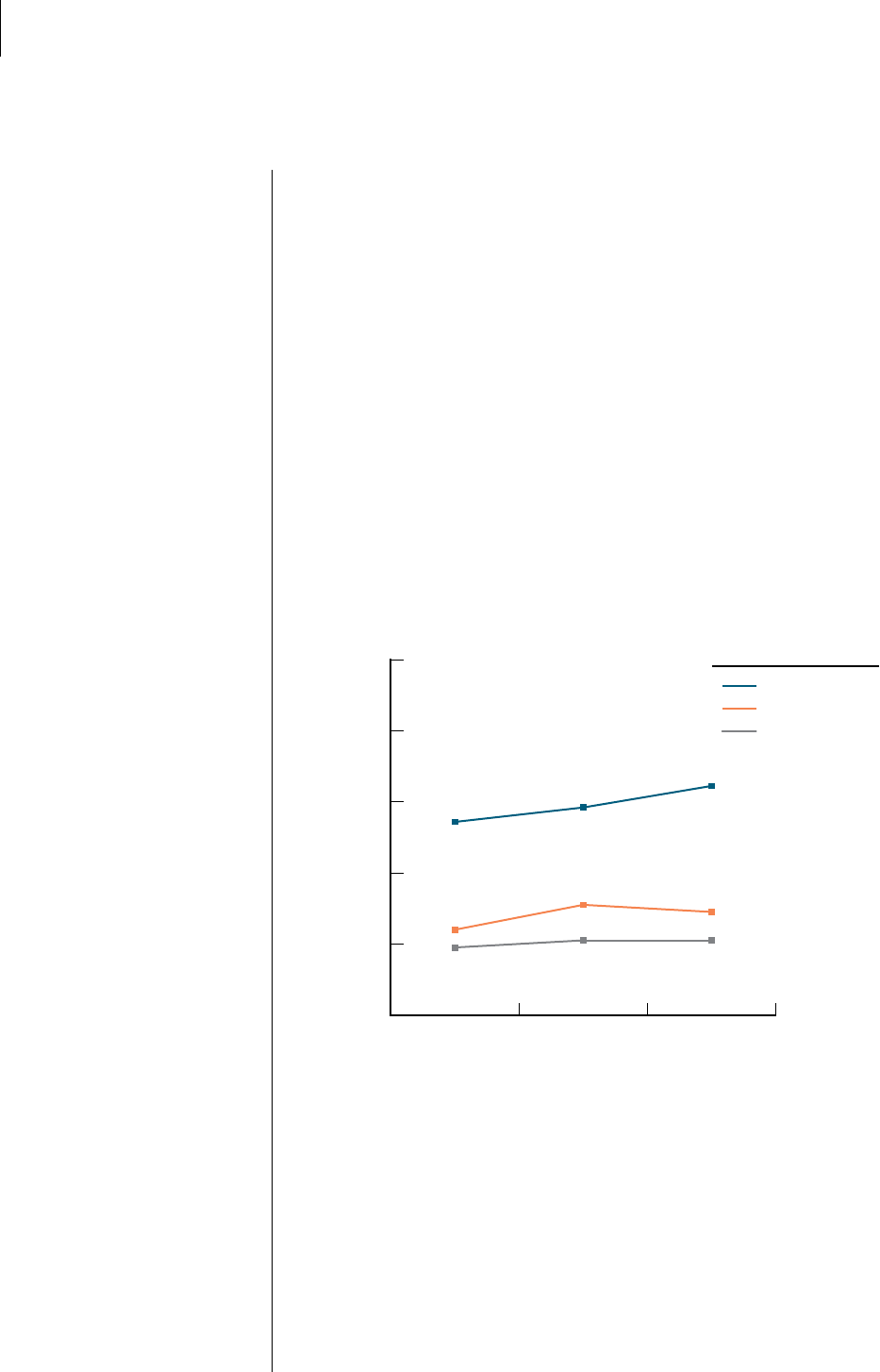

Figure 4

Most Students Who Fell Off Track Did So in Grade Nine

Graduation Years2013Through2015

Year of High School

12th Grade11th Grade10th Grade9th Grade

Percentage of Students

Who Fell Off Track

0

20

40

60

80

100%

9%

16%

5%

9%

13%

7%

11%

15%

8%

72%

56%

80%

Coachella Valley

San Francisco

Stockton

UNIFIED SCHOOL DISTRICT

Source: California State Auditor’s analysis of student data provided by Coachella Valley, SanFrancisco, and Stockton Unified School Districts.

Notes: We calculated the number of students who fell off track to meet college preparatory requirements during each year of school for students in

graduation years2013 through2015.

We excluded students who left the district.

Percentages may not add to 100 due to rounding.

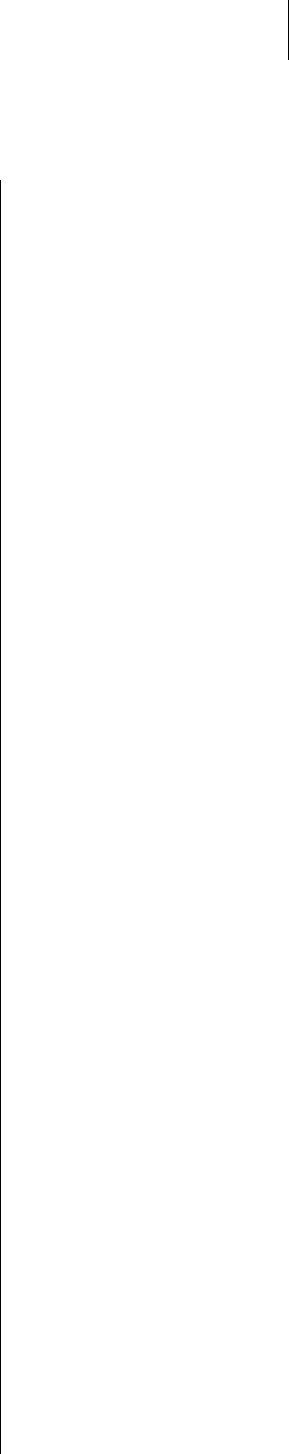

Our analysis shows that students struggled most significantly

with English and math courses—the twosubject areas which

CSU and UC require be taken for the most years. As Figure on

page shows, we found that for students in graduation years

through, about percent of students in Stockton and

Coachella did not meet the English and math college preparatory

course requirements. In SanFrancisco, about percent of students

didnot meet these requirements. We found that, on average,

percent of Stockton students, percent of Coachella students,

and percent of SanFrancisco students did not pass a college

preparatory English class by the end of gradenine. Further, on

average, about percent of students in Stockton, percent of

students in Coachella, and percent of students in SanFrancisco

had not passed a college preparatory math class by grade.

19California State Auditor Report 2016-114

February 2017

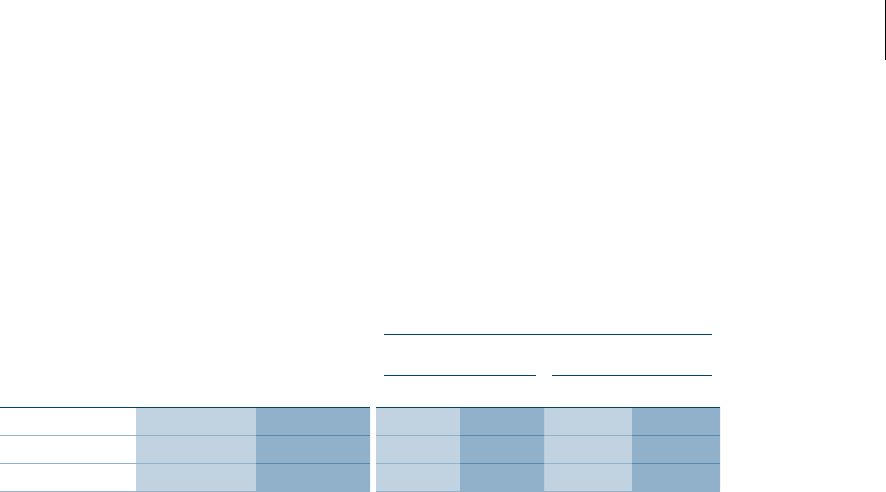

Figure 5

Most Students Who Fell Off Track in Grade Nine Did Not Complete College PreparatoryCoursework

Graduation Years 2013 Through 2015

48%

38%

14%

11%

29%

74%

20%

6%

64%

28%

8%

60%

32%

8%

65%

32%

3%

60%

38%

59%

3%

56%

34%

10%

22%

72%

6%

Met requirements

Did not meet

requirements

Left district

Results of Students Who Were

On Track in Ninth Grade

at the End of High School

On track

Off track

Left district

Percentage of Students

On or Off Track at the

End of Ninth Grade

Met requirements

Did not meet

requirements

Left district

Results of Students Who Were

Off Track in Ninth Grade

at the End of High School

Stockton

Unified School District

San Francisco

Unified School District

Coachella Valley

Unified School District

Source: California State Auditor’s analysis of student data provided by CoachellaValley, SanFrancisco, and Stockton Unified SchoolDistricts.

California State Auditor Report 2016-114

February 2017

20

Many Stockton and Coachella students needed additional assistance

in gradenine to pass some college preparatory courses. Districts

offer support classes to provide supplementary or preventative

assistance to help students successfully complete college preparatory

coursework. Districts enroll students in these support courses when

they determine that students are not academically prepared for

college preparatory coursework. ese classes can be taken before

enrolling in a college preparatory course or simultaneously. We

reviewed districts’ enrollment figures for support classes and found

that an average of percent of Coachella’s gradenine students

enrolled in a math support class and percent of gradenine

students enrolled in an English support class. e executive

curriculum director at Stockton indicated that a barrier to college

preparatory coursework completion is a lack of students adequately

prepared for grade level coursework as freshmen. In Stockton, the

district identified math support courses in which percent of its

gradenine students were enrolled. In contrast, SanFrancisco’s policy

is to automatically enroll students in college preparatory courses,

rather than supportcourses.

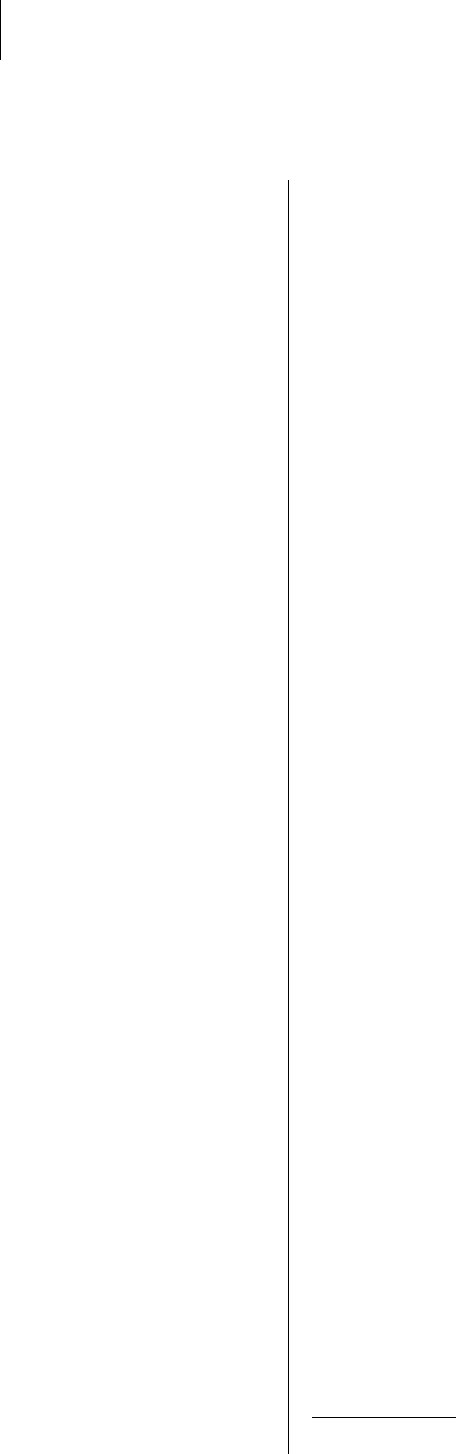

e percentage of students enrolled in college preparatory courses

does not appear to have a significant impact on completion rates.

ere is not a noteworthy gap between districts related to the

percentage of students enrolled in college preparatory courses.

As Figure on page shows, SanFrancisco enrolled an average

of only percent more of its gradenine students in college

preparatory English courses than did Stockton for graduating years

through. Given that SanFrancisco’s completion rate is

considerably higher than Coachella’s and Stockton’s, it appears that

factors other than the enrollment rates in those courses influenced

completionrates.

Funds to help kindergarten through gradeeight students prepare

for the rigor of college preparatory coursework could help keep

more high school students on track to complete the coursework

requirements by their senior year. In the Legislature approved

a similar funding strategy for high school students. e College

Readiness Block Grant (Block Grant) allocated million to

provide additional support to high school students, particularly

unduplicated students, to increase the number of students who

enroll in institutions of higher education and complete a bachelor’s

degree within fouryears. Districts could use those funds for

support activities such as professional development, counseling

programs, and programs to expand access to classes to satisfy the

college preparatory courseworkrequirements.

Many Stockton and Coachella

students needed additional

assistance in grade nine to pass

some college preparatorycourses.

21California State Auditor Report 2016-114

February 2017

Figure 6

English and Math Requirements Presented the Greatest Challenge to Students

Graduation Years 2013 Through 2015

Subject Area

College

Preparatory

Elective

Visual and

Performing

Arts

Foreign

Language

Lab

Science

MathEnglishHistory

GFEDCBA

Percentage of Students

0

20

40

60

80

100%

Subject Area

College

Preparatory

Elective

Visual and

Performing

Arts

Foreign

Language

Lab

Science

MathEnglishHistory

GFEDCBA

Percentage of Students

0

20

40

60

80

100%

Subject Area

College

Preparatory

Elective

Visual and

Performing

Arts

Foreign

Language

Lab

Science

MathEnglishHistory

GFEDCBA

Percentage of Students

0

20

40

60

80

100%

31% 58% 59% 48% 45% 25% 25%

69% 42% 41% 52% 55% 75% 75%

Not Met

Met

COLLEGE PREPARATORY

COURSEWORK REQUIREMENTS

10% 23% 24% 13% 17%

6%

4%

90% 77% 76% 87% 83% 94% 96%

31% 61% 64% 49% 46% 25% 14%

69% 39% 36% 51% 54% 75% 86%

Stockton

Unied School District

San Francisco

Unied School District

Coachella Valley

Unied School District

Source: California State Auditor’s analysis of data provided by CoachellaValley, SanFrancisco, and Stockton Unified SchoolDistricts.

Note: We excluded students who left the district.

22 California State Auditor Report 2016-114

February 2017

Figure 7

Average Enrollment Rates in College Preparatory Math and English Courses in Grade Nine Did Not Vary

Significantly

Graduation Years 2013 Through 2015

Unified School District

StocktonSan FranciscoCoachella Valley

Percentage of Students Enrolled

0

20

40

60

80

100%

92%

92%

97%

95%

83%

88%

English

Math

SUBJECT AREA

Source: California State Auditor’s analysis of student data provided by Coachella Valley, SanFrancisco, and Stockton Unified SchoolDistricts.

SanFrancisco presented a plan for its Block Grant that focused on

college counseling, city college dual enrollment efforts, and using

micro funding tailored to meet individual school needs. Stockton’s

approach included increasing services to high school students,

specifically its unduplicated students, through increased staffing

oversight, covering assessment fees for standardized tests for

college admission, and assigning a dedicated mentor to incoming

students to support them throughout their high school experience.

Stockton plans to establish a freshman boot camp to support

incoming students, followed by field trips to colleges. Students

would have the opportunity to meet with counselors who review

assessments and transcripts. Stockton also plans to enhance its

data collection efforts to measure the effectiveness of its plans.

According to the director of state and federal projects at Coachella,

the district has yet to submit its plan to Education, but plans to do

so in February. We believe that similar funding and support

strategies targeted at kindergarten through gradeeight students

could help prepare California’s students for meeting the minimum

coursework requirements needed for admission to UC andCSU.

23California State Auditor Report 2016-114

February 2017

Although the Schools We Reviewed Appear to Have Provided

Sufficient Access to College Preparatory Coursework for Certain Years,

the Data Were SignificantlyLimited for Other Years

State law requires school districts that maintain any grades

fromseven to inclusive to offer all of their students coursework

that will allow them to meet the minimum requirements for

admission to California’s public postsecondary educational

institutions. To evaluate whether sufficient access existed, we

reviewed the percentage of total courses offered at each of the

threedistricts we visited, and found that the percentages did not

vary significantly among the districts. Specifically, in–,

percent and percent of all the courses offered at Coachella

and Stockton, respectively, were college preparatory courses. In

SanFrancisco, this percentagewas. We also conducted a detailed

course-by-course analysis by reviewing the schedules of courses

offered at two high schools in each of threeschool districts and

compared the courses offered to the schools’ enrollments. When

the schools had maintained the information we needed, we found

that they had provided students with sufficient access to college

preparatory coursework. is finding suggests that access did not

present a significant barrier to the completion of college preparatory

courses. However, fourof the sixhigh schools were unable to supply

us with the data necessary to determine that they had provided

sufficient access for all years in our auditperiod.

e data available suggests that adequate capacity existed to allow

students to take the full range of college preparatory requirements

during gradesnine through at the sixschools we selected. For

example, to allow students to take the required fouryears of college

preparatory English, traditional semester-based high schools

should offer access to these classes for percent of their students

every year. e twoschools in Coachella exceeded this obligation

during the years for which data were available: Coachella Valley

High School provided a sufficient number of seats for percent

of its students in –, and Desert Mirage High School

provided enough seats for percent of its students in –

as AppendixA beginning on page demonstrates. Likewise,

SanFrancisco offered seats for more than percent of its

students at Mission and Washington high schools during –

and –—the years for which the schools were able to provide

usabledata.

In Stockton, however, Franklin High School satisfied the minimum

English access requirement by enrolling students past the maximum

capacity of students per section. For example, Franklin High

School overenrolled students in different English sections.

e Franklin High School principal did not respond to our

numerous requests for perspective on this issue. Moreover, during

When the schools had maintained

the information we needed, we

found that they had provided

students with sufficient access to

college preparatorycoursework.

California State Auditor Report 2016-114

February 2017

24

that same period, Franklin High School enrolled students in other

college preparatory courses, such as chemistry and earth science,

beyond the maximum capacity for sections of those courses. We also

reviewed course enrollments during – at George Washington

High School in SanFrancisco and Desert Mirage High School in

Coachella. At George Washington High School, we found students

overenrolled in college preparatory sections, and at Desert Mirage

High School we identified fourstudents who were overenrolled. us,

although these high schools technically met the access requirement—

Franklin High School in particular—they did so in a manner that

may have negatively affected the success of all the students in those

overenrolledsections.

Furthermore, although each high school we reviewed did not meet

the minimum access requirements in every category for every

year, as TableA beginning on page in Appendix A shows, these

deficiencies were unlikely to have affected students’ opportunities

to complete all of the college preparatory requirements. For

example, several schools failed to meet the minimum two-year

foreign language requirement. However, admissions criteria allow

students to take only oneyear of a foreign language if it is a higher

level course, potentially decreasing the number of foreign language

courses that schools need to offer.

5

In other instances, schools

that did not offer enough college preparatory elective classes had

excess capacity in other course categories such as English or foreign

language, so students could take those courses to satisfy their elective

requirements. TableA includes explanations for why some schools’

failure to meet certain access targets likely did not harmstudents.

Additionally, we verified that all of our selected schools other than

Coachella Valley High School offered courses with sufficient frequency

so that students had the ability to take the courses they needed during

the school day in –. In other words, we did not identify any cases

in which a school offered all courses for multiple categories—such as

English and math—during the same period of the day. us, the times

at which schools offered courses did not present a barrier to students’

access to those classes for–. We were unable to verify that

Coachella Valley High School offered courses with sufficient frequency

throughout the school day because it did not retain thisinformation.

e manner in which our selected schools built their course schedules

likely resulted in them offering sufficient access to college preparatory

courses for the years we were able to review. e schools within

our selected districts asserted that each year they used a number

of factors to build their course schedules, including schedule types,

5

There are several other ways to validate the foreign language requirement, including certification

by a high school principal and assessment by a college oruniversity.

We did not identify any cases in

which a school offered all courses

for multiple categories—such as

English and math—during the

same period of theday.

25California State Auditor Report 2016-114

February 2017

graduation requirements, and student requests. ese factors enabled

the schools to determine which college preparatory courses students

wanted or needed each year. When we spoke with other districts,

including SanDiego Unified and Vallejo City Unified, they stated

that—similar to SanFrancisco—they provide sufficient access based

on college preparatory-aligned graduationrequirements.

Although we were able to reach certain conclusions about

course access at the sixhigh schools we selected, significant data

limitations impeded our ability to definitively determine whether

the schools in the districts we reviewed provided adequate course

access for each year we reviewed from– through–.

For example, SanFrancisco’s former data system, which it used

through–, did not track whether the courses it offered

were for a semester or a full year. Coachella’s practice has been to

mark courses that ended before the final term of the school year as

inactive, which made it appear that Coachella failed to offer courses

even though it did actually offer them. Stockton, as we discuss later,

incorrectly marked courses as college preparatory coursework

certified, even though UC had not certified them. However, our

review did not address whether the districts as a whole were

offering appropriate levels of access to college preparatory courses

because that would require evaluating every high school in

thedistrict.

Districts would need to conduct analyses similar to what we

performed to demonstrate they are offering appropriate levels of

access; however, none of the three we reviewed have done so. e

data limitations we identified serve to illustrate the improvements

in data retention and analysis that would be necessary for districts

to demonstrate whether they provide all students with required

access to college preparatory coursework. Without the proper data

systems and processes in place, the districts cannot demonstrate to

their stakeholders that they are complying with statelaw.

Although Achievement Gaps Exist in All Three Districts We Reviewed,

Certain Subgroups of Students Fared Better in SanFrancisco Than in

Coachella andStockton

In all threedistricts we reviewed, we identified achievement gapsin

completing college preparatory coursework; however, certain

subgroups of students—such as underrepresented minorities,

and English learners—generally fared better in SanFrancisco

than in Coachella or Stockton.

6

As we show in Figure, on the

6

We used UC’s definition for underrepresented minorities. Specifically, UC considers

underrepresented minorities to be Chicanos/Latinos, African Americans, and AmericanIndians.

Significant data limitations impeded

our ability to definitively determine

whether the high schools in the

districts we reviewed provided

adequate course access for each year

wereviewed.

26 California State Auditor Report 2016-114

February 2017

following page, for students in graduation years through,

underrepresented minorities’ completion rates in SanFrancisco

ranged from percent to percent.

7

ese rates were generally

less than half of those of white and Asian students, ranging from

percent to percent. Stockton’s achievement gap narrowed for

students in graduation years through due to the declining

completion rate among white and Asian students. Stockton’s

underrepresented minorities’ completion rates ranged from

percent to percent, whereas completion rates for white and

Asian students ranged from percent to percent. In Coachella,

the completion rates for underrepresented minorities ranged from

percent to percent.

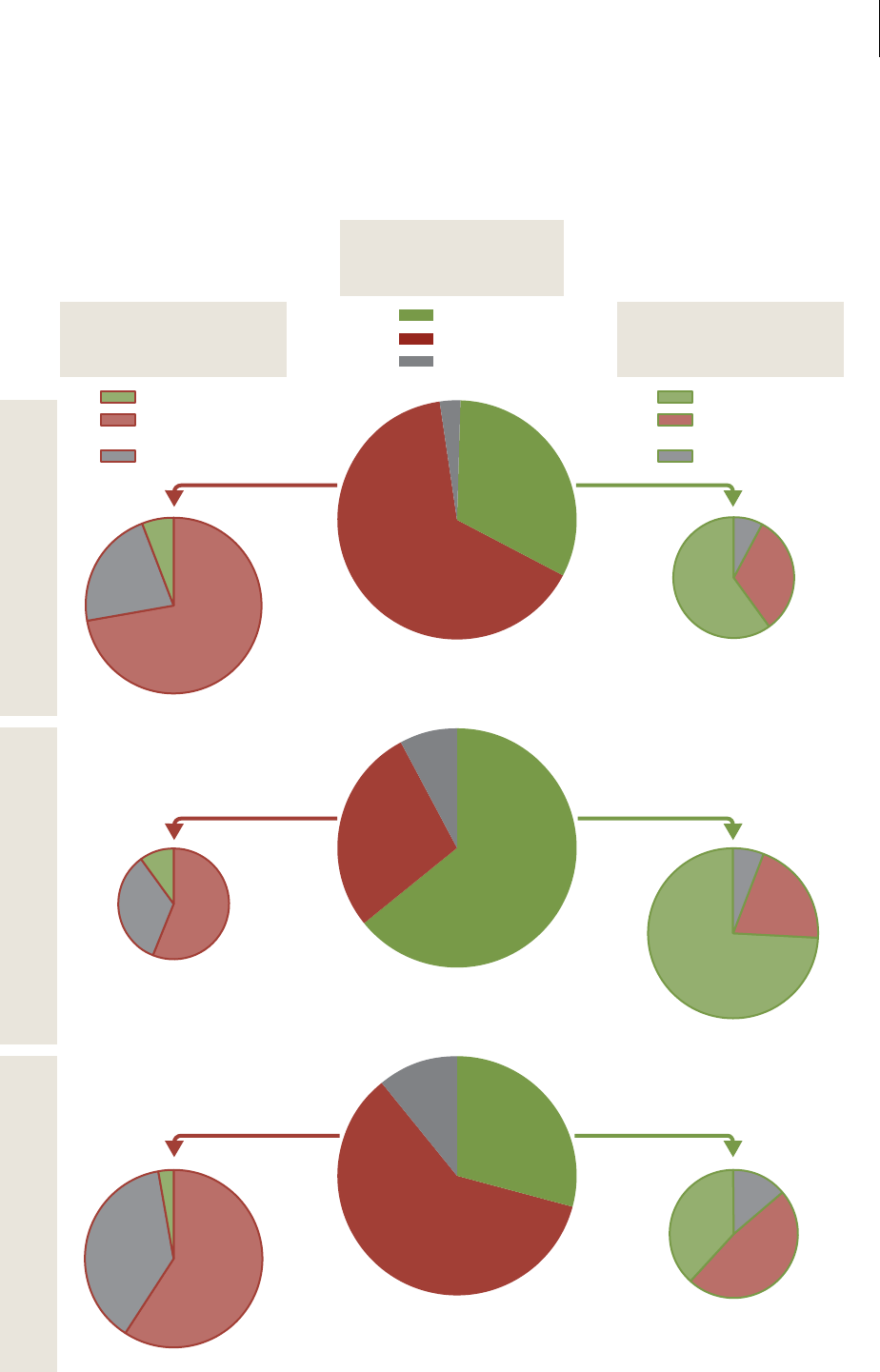

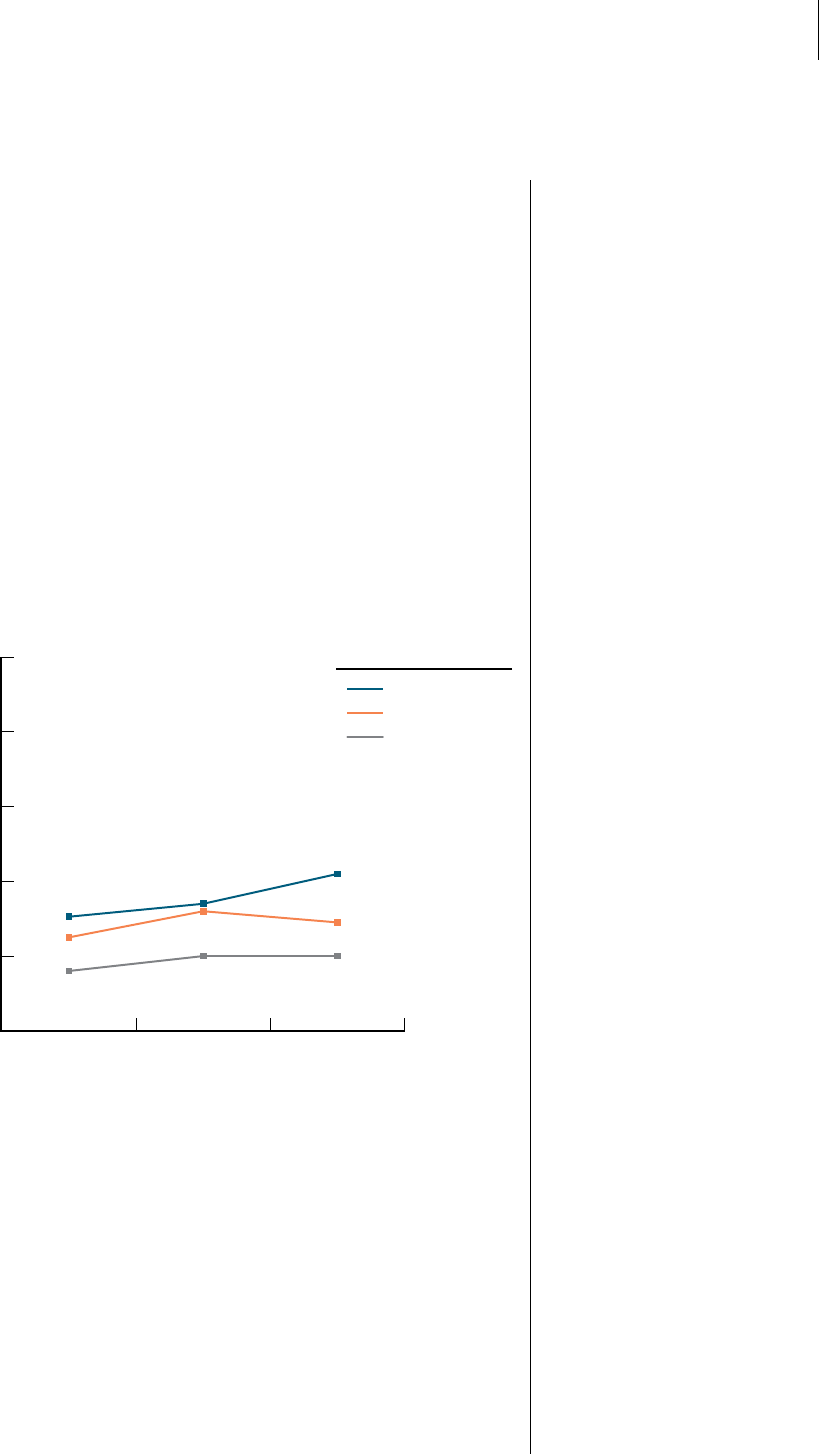

Figure 8

Completion Rate Achievement GapsExist Among Demographic Subgroups

Graduation Years 2013 Through 2015

San Francisco—White/Asian

San Francisco—Underrepresented Minorities

Coachella Valley—Underrepresented Minorities

Stockton—White/Asian

Stockton—Underrepresented Minorities

UNIFIED SCHOOL DISTRICT AND STUDENT DEMOGRAPHIC

Graduation Year

201520142013

College Preparatory Coursework

Completion Rate

0

20

40

60

80%

72%

73%

78%

25%

31%

29%

26%

31%

41%

26%

29%

25%

17%

19% 19%

Source: California State Auditor’s analysis of student data provided by CoachellaValley, SanFrancisco, and Stockton Unified SchoolDistricts.

Notes: We did not include students who identified as white or Asian in Coachella because the subgroup is made up of fewer than 50students.

State law instructs the California Department of Education to report completion rates only for subgroups whose population exceeds

50students.

For the purpose of this analysis, we used the University of California’s (UC) definition for underrepresented minorities. Specifically, UC considers

underrepresented minorities to be Chicano/Latino, African American, and AmericanIndian.