What are our stories worth? | Measuring the economic and cultural value of Australia’s screen sector

i

What are our stories worth?

Measuring the economic and cultural value

of Australia’s screen sector

ii

What are our stories worth? | Measuring the economic and cultural value of Australia’s screen sector

iii

Key ndings v

Executive summary 1

1. Introduction 7

2. Economic contribution analysis 12

3. Exports and tourism 23

4. Audience value 29

5. Cultural value 38

References 44

Appendix A – External stakeholders 47

Appendix B – Government support 48

Appendix C – Survey results 49

Appendix D – Consumer choice value

and time-use elasticity 50

Appendix E – Economic contribution studies 52

Limitation of our work 55

Contents

What are our stories worth? | Measuring the economic and cultural value of Australia’s screen sector

iv

ABC Australian Broadcasting Corporation

ABS Australian Bureau of Statistics

ACMA Australian Communications and Media Authority

AHEDA Australian Home Entertainment Distributors Association

ASTRA Australian Subscription Television and Radio Association

CV Contingent Valuation

DVD Digital Versatile Disc

EBITDA Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation and Amortisation

FTE Full-time equivalent

GDAA Game Developers’ Association of Australia

GDP Gross Domestic Product

GOS Gross Operating Surplus

IGEA Interactive Games & Entertainment Association

IMAX Image Maximum

IO Input Output

MEAA Media Entertainment & Arts Alliance

MPDAA Motion Picture Distributors Association of Australia

NAIDOC National Aboriginal and Islander Day Observance Committee

OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

PC Personal computer

PDV Post, Digital and Visual Eects

SBS Special Broadcasting Service

SOCOG Sydney Organising Committee for the Olympic Games

SVOD Subscription Video on Demand

TRA Tourism Research Australia

TV Television

UK United Kingdom

US United States

VHS Video Home System

VOD Video on demand

Glossary

v

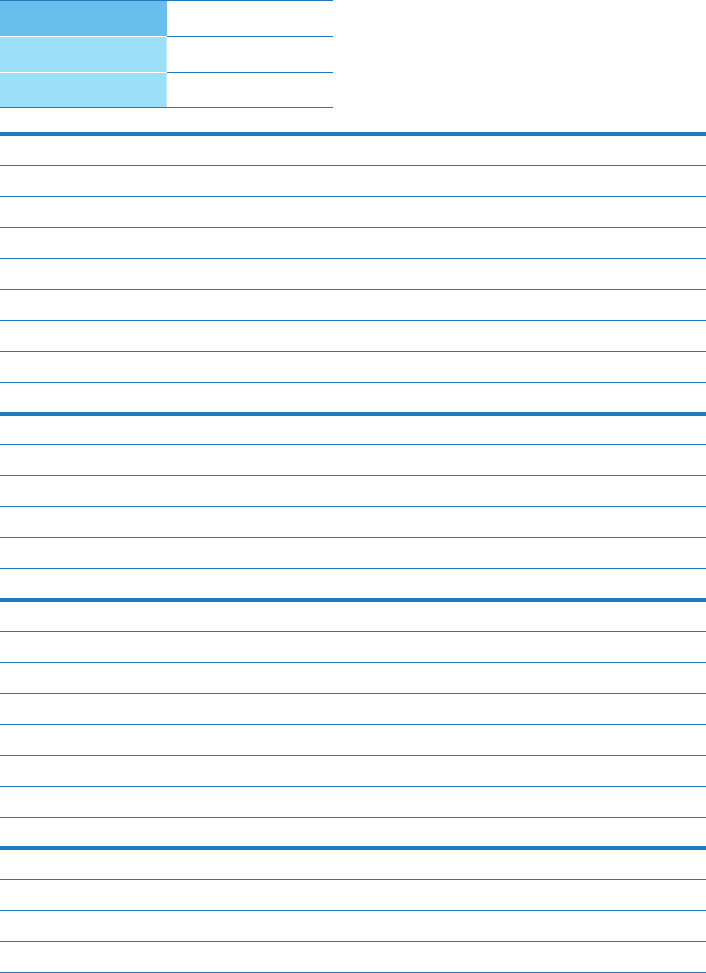

Key ndings

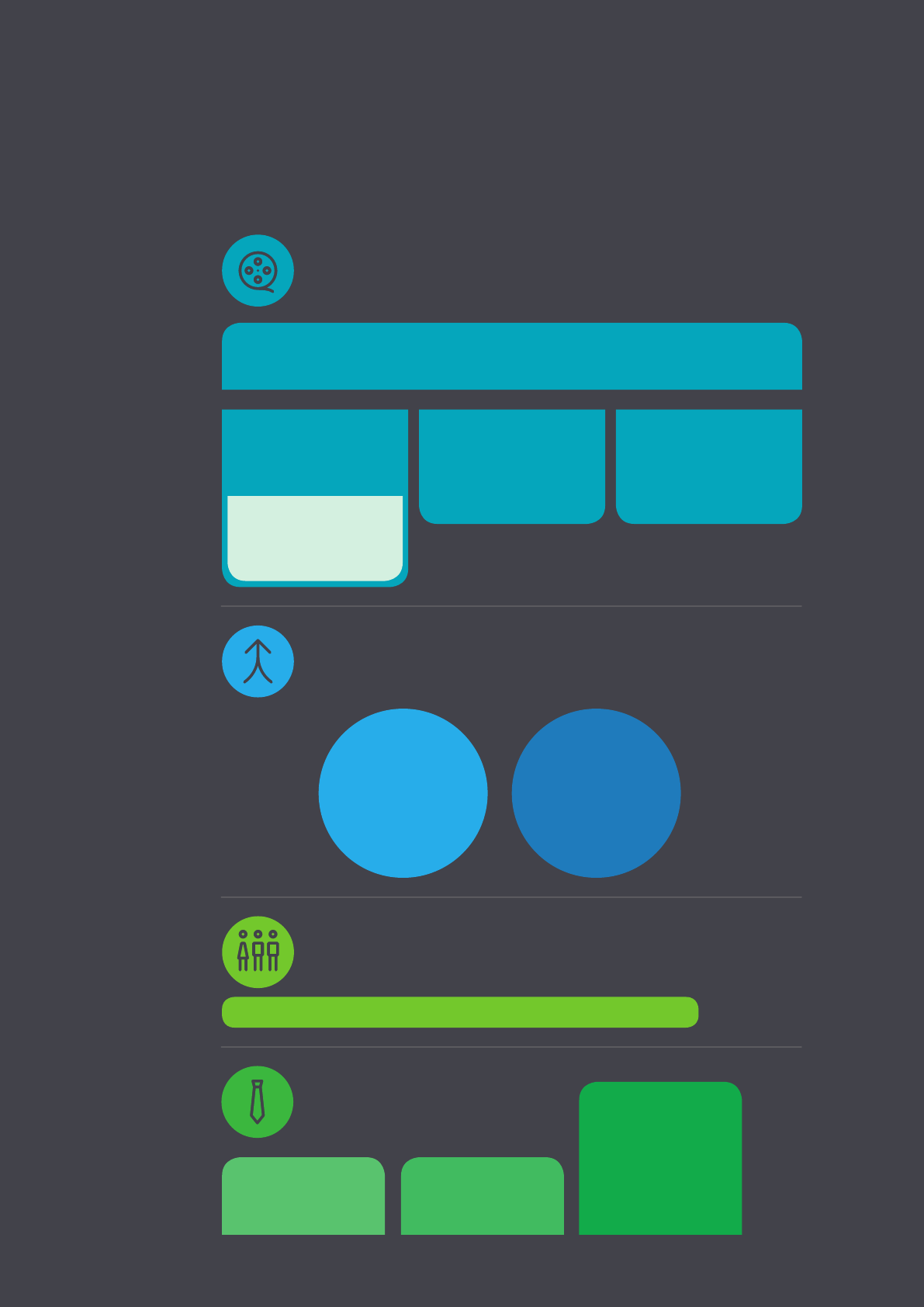

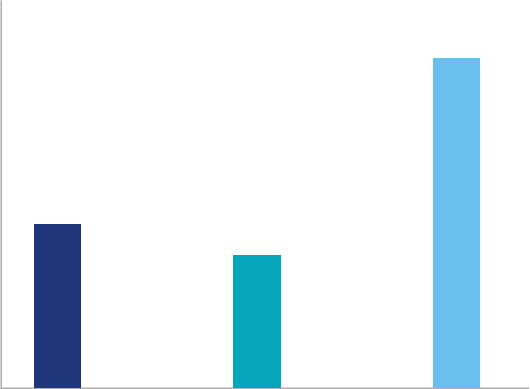

Audience value

2014 –15

$17.4 billion in total audience value of broad screen content

Cultural value

Option value

$511 million a year

Existence/

altruism value

$415 million a year

Public support value

$1.02 billion a year

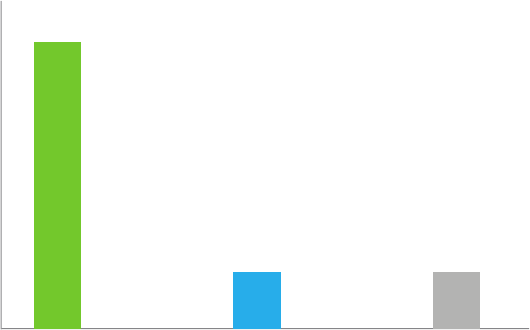

Economic contribution

2014 –15

$3,072 million in value add

25,304 FTE jobs

Broad screen content

$3,072 million in value add

25,304 FTE jobs

Footloose production

$382 million in value add

4,093 FTE jobs

Digital games production

$123 million in value add

1,053 FTE jobs

Core screen content

$847 million in value add

7,650 FTE jobs

Exports and tourism

2014 –15

Exports

$252 million

in total export

earnings from core

screen content

Tourism

$725 million in

tourism expenditure

associated with

broad screen

content

What are our stories worth? | Measuring the economic and cultural value of Australia’s screen sector

1

The Australian screen sector plays a signicant role in the economy in terms of its contribution to GDP and to

national employment, as well as its economic contribution to downstream industries such as exhibition and

retail, and to ancillary sectors such as tourism. The Australian screen sector is also an enduring component

of Australia’s cultural identity. Indeed, screen content also stands apart from all other Australian cultural

products in its unparalleled ability to reach large audiences, both domestically and abroad.

The importance of its contributions in these areas are widely recognised by government, which is why the

sector is supported through funding and regulation. However, the nature and size of these contributions in

economic terms has never been fully recognised until now.

Screen Australia engaged Deloitte Access Economics to develop a framework capable of comprehensively

capturing the value generated by the Australian screen sector. The framework considered this value across a

number of dimensions – economic, audience and cultural.

Australian screen content is a signicant contributor to the nation in terms of gross domestic product

and jobs, and well-positioned to help grow Australia’s creative economy.

The Australian screen sector contributes signicantly to national gross domestic product and employment

(which are more traditional measures of a sector’s value to an economy). Content is created by the

production subsector, enters the distribution subsector and is purchased in the exhibition, free-to-air TV, pay

TV, retail, rental and online subsectors.

Australian TV content encompasses a wide range of production activity – it includes ctional or drama

production (such as mini-series, drama shows, comedy shows and children’s TV shows), as well as factual

documentaries. The remainder is allocated to content such as news, current aairs, light entertainment,

reality, and sport. Likewise, feature lm content in Australia covers a range of content – from ones with large

international releases to ones that have been domestic box oce and/or critical successes to more low-

budget lms and lms with limited local releases.

This study focussed in on the ‘Australian’ fabric of the wider screen industry, examining the value generated

by screen content developed under the creative control of Australians.

1

We note that this study is not a full

benet-cost analysis and doesn‘t look at potential costs associated with screen consumption.

Two denitions were employed. The rst denition, Broad Australian content, is screen content that is

made under the creative control of Australians, which includes feature lm, drama TV and documentaries

as well as other types of screen content. This includes (but is not limited to) news and current aairs, light

entertainment, reality shows, lifestyle/food/travel shows and televised sports content.

In 2014-15, the total economic contribution of the Australian screen sector for Broad Australian content is an

estimated $2.6 billion in value add and almost 20,160 in FTE jobs. This total value add is the equivalent

Executive summary

1 Previous studies have estimated the overall size of the screen size of screen sectors in Australia. For example, see Deloitte

Access Economics (2015a) “Economic contribution of the lm and television industry in Australia”, a prepared for the Australian

Screen Association; and “Economic contribution of screen production in South Australia”, reported prepared for the South

Australian Film Corporation Deloitte Access Economics (2015b).

What are our stories worth? | Measuring the economic and cultural value of Australia’s screen sector

2

of around 5% of Australia’s information media and telecommunications industry or 18% of its arts and

recreation services.

2

The second denition, Core Australian content, is screen content made under the creative control of

Australians and is scripted, narrative content, capturing feature lm, drama TV and documentaries only.

3

As such, Core screen content sits within the scope of Broad screen content.

In 2014-15, the total economic contribution of the Australian screen sector for Core Australian content is an

estimated $847 million in value add

4

and 7,650 in full-time equivalent (FTE) jobs. This total value add is

the equivalent of around 7% of Australia’s arts and recreation services industry. Free-to-air ($212 million) and

lm and television production ($153 million) were the largest contributing subsectors to estimated direct value

add, with the production subsector the greatest contributor to employment (2,683 in estimated FTE jobs).

International footloose productions hire skilled Australian workers

Additional to the contributions already identied are those generated for the Australian economy

through footloose productions – that is, television and lm production activity occurring in Australia

as a result of large budget, international-studio nanced productions choosing to lm in Australia

instead of elsewhere.

The total economic contribution of footloose productions in Australia for 2014-15 is estimated at $382

million in total value add and around 4,090 in FTE jobs. The benets of this activity are largely

derived through labour income paid to Australian creative talent (i.e. cast and crew) and indirectly

through the reach of supply chains into other sectors.

The 2014-15 year was an unusually large year for Australia (with $418 million in foreign spending across the

feature lm and TV drama slate), with the ve year average being $196 million from 2010-11 to 2014-15.

5

There are export opportunities for the content created locally by Australians

In 2014-15, total export earnings from Core Australian content were approximately $252 million

6

(approximately equivalent in size to Australia’s sugar and honey product exports or a tenth of medicinal

and pharmaceutical product exports in 2014-15). This comprises mainly international box oce earnings

that accrue to Australia, although international royalties was also a signicant export sources.

7

2 Information media and telecommunications incorporates publishing and broadcasting (including internet), motion picture

and sound recording, internet and data processing services, library and information services and telecommunication services.

Arts and recreation services incorporates heritage activities, creative and performing arts, sports and recreation services and

gambling services.

3 Core Australian content is a key focus of Screen Australia. This includes Australia’s feature lms (e.g. Mad Max: Fury Road, The

Dressmaker); documentary lms (e.g. That Sugar Film, Frackman); TV documentaries (e.g. First Contact, Go Back To Where You Came

From); TV drama, which encompasses a diverse range of content, such as mini-series (e.g. The Secret River, Deadline Gallipoli),

dramas (e.g. Jack Irish, Underbelly), comedy shows (e.g. Upper Middle Bogan, The Family Law) and children’s TV shows (e.g. Nowhere

Boys, Dance Academy).

4 Value add measures the value of output (i.e. goods and services) generated by the entity’s factors of production (i.e. labour

and capital) as measured by the income to those factors of production. The sum of value add across all entities in the economy

equals gross domestic product.

5 Screen Australia (2015a) Drama Report data on footloose production expenditure..

6 It should be noted that these export earnings are not additive with the economic contribution gures for Broad and Core, as

they are revenue to the sector that has already been counted in the contribution estimates.

7 The licence fee data used in this analysis only takes into account Screen Australia funded rst releases, meaning that the export

earnings gure here should be interpreted as a lower bound on export earnings. Exports of Core Australian content are likely to

be even higher than presented here.

What are our stories worth? | Measuring the economic and cultural value of Australia’s screen sector

3

Australian screen content also includes digital games content produced in Australia.

8

Game developers

in Australia are predominantly small to medium-sized independent studios and studios of international

publishers. The games they produce are primarily exported to the global market. In 2014-15, the total

economic contribution of digital game production in Australia was around $123 million in value add and

almost 1,055 in FTE jobs.

9

Taken together, the Broad screen sector, digital games production and footloose production contribute over

$3 billion in value add and around 25,300 in FTE jobs. This is in contrast to the modest funding the screen

sector receives from government sources.

The role of advertising

While not examined in terms of its economic contribution, the advertising industry also plays an

important role with regards to Australian screen sector activities. Advertising:

• Funds a signicant amount of Broad and Core screen content, such as through advertising revenue

earned by free-to-air TV broadcasts. According to ZenithOptimedia forecasts, Australia’s television

advertising revenue is expected to reach just under $4 billion in 2016 (Mason, 2016).

• Serves as an important adjacency to the production subsector, as cast and crew employed in the

Broad and Core screen sector also earn income from advertising work and many technical and

creative screen professionals that eventually end up in Australian lm and TV productions were initially

trained through working on advertisements.

Australian-produced content dominates in terms of free-to-air television ratings. According to

consolidated OzTam ratings data across ve metropolitan markets (Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane,

Adelaide and Perth), the highest rated non-sports shows were the nal episodes of MasterChef, My

Kitchen Rules and The Block, with 2 million views and over (Knox, 2016a). In light of this, it is apparent

that Australian content is associated with a large amount of advertising revenue which accrues to the

commercial free-to-air television subsector.

The exposure of Australian content to international audiences is also powerful in strengthening the

brand value of Australia, assisting it to grow a compelling image as a destination for tourism.

The value of screen in drawing tourists to visit a particular destination is widely acknowledged.

10

This trend is

called “set-jetting”, where screen reaches the mass population, drawing them to a destination or attraction

specically to visit a location where a lm or TV program was shot. Screen can even drive tourist visitation

through its portrayal of the features and characteristics of the destination in which shoot itself takes place

(e.g. landscapes and attractions). Australian screen content, screen actors and practitioners with a strong

international prole can also help promote the Australian brand and bring attention to the country as a

potential location for tourism.

A survey commissioned by Deloitte Access Economics for this study reveals that around 230,000

international tourists are estimated to visit or extend their stay in Australia each year as a result of viewing

Australian lm and TV content. This represents around $725 million in estimated tourism expenditure in

Australia each year that may be associated with Australian screen content.

8 This includes content produced for mobile and tablet games (e.g. Flight Control, Real Racing, Fruit Ninja, Crossy Road) and PC

and console games (e.g. Don Bradman Cricket, Rugby League Live 3).

9 This gure relates to the production of digital games alone and does not include publishers/distributors and retail, rental or

online subsectors that are further along the value chain for the Australian games sector.

10 For example, see Olsberg SPI, 2015; Olsberg SPI & Nordicity, 2015; Noridicity, 2013; Beeton, 2006.

What are our stories worth? | Measuring the economic and cultural value of Australia’s screen sector

4

This suggests that screen content as a driver of tourism is comparable to other iconic drivers and may be a

signicant driver of tourism to the country. For example, a Deloitte Access Economic (2013a) report on the

Sydney Opera House found that the Sydney Opera House could be responsible for around $640 million of

tourism expenditure in Sydney in 2012–13.

11

There is more to the value of Australian screen content than observable market transactions.

Domestic audiences also gain surplus value that far exceeds the economic contributions, exports and

tourism expenditure values.

The value of Australian screen content extends beyond the earnings it accrues from market transactions or

its value add and employment. Australian lm and TV content also generates signicant entertainment and

leisure value to domestic audiences. This value to audiences can be estimated as a monetary value.

The value of screen content to audiences can be measured in two ways. Firstly, it can be measured as a

combination of revenue from consumers to the screen sector, such as ticket sales, combined with any

‘consumer surplus’ benet above what people paid. Secondly, it can be measured by the value of time

spent watching Australian screen content, which is particularly useful in instances where the content is

free to watch.

Using a mixture of these two approaches, this report nds that the total audience value of Australia’s

Broad lm and TV content viewing in 2014-15 was approximately $17.4 billion in consumer welfare

benet, almost seven times the size of the total value add for Broad Australian content. Moreover,

by way of comparison, total Australian industry value added in 2014-15 was around $12.8 billion for arts and

recreation services.

Australian screen content is considered unique

In estimating the audience value, it was found that Australian screen content was unique – almost two

thirds (64%) of Australian lm and TV content was considered to be ‘fairly’, ‘very’ or ‘completely’ dierent

from foreign content based on qualities such as storyline, setting, acting music and camera work.

Further still, Australian screen content generates a valuable contribution to the cultural landscape –

widely recognised, though a value indirectly measured through people’s appraisal of Australian lm

and television.

Cultural value generated by Australian screen content has value in terms of its contribution to the overall

cultural environment of the country. For example, local lm and TV can support creative and artistic ventures,

such as the acting, music, writing and set design.

The value of individuals personally having the option of viewing Australian content in the future – known as

the “option value” – is estimated to be approximately $511 million a year. Similarly, the value that individuals

place on other people being able to watch Australian content in the future – known as the “existence” or

“altruism value” – is estimated to be approximately $415 million a year.

11 It should be noted that while this is not directly comparable with the screen-induced tourism expenditure across entire country

due to the fact that the Sydney Opera House report reports the amount of expenditure attributable to only Sydney tourism

expenditure, this provides a point of comparison between tourism attributable to screen content and a major driver of tourism

in Australia.

12 It should be noted that public support value for Australian TV and lm content can also be aected by a number of factors – for

example, respondents may think that higher levels of government support will reduce the purchasing price of future Australian

lms and TV shows.

What are our stories worth? | Measuring the economic and cultural value of Australia’s screen sector

5

Further, when individuals were asked how much government should allocate between lm and TV and a

maximum of a $100 tax cut in the survey, the results suggests that the total public support value of Australian

lm and TV to be approximately $1.02 billion a year.

12

For comparison, direct funding from government sources for Australian feature lm and drama TV in

production in 2014-15 was approximately $58 million, support through the Producer Oset came to $77

million and the PDV Oset for TV was over $7 million.

13

In addition, documentaries received $25 million in

direct funding and $18 million through the Producer Oset in 2014-15.

14

Further, government expenditure in

2014-15 in public broadcasting came to around $1.43 billion.

15

Deloitte Access Economics

13 Screen Australia (2015a) Drama Report data

on funding sources for feature lm and

drama TV.

14 Screen Australia (2016b) “Documentary

Finance”, http://www.screenaustralia.

gov.au/fact-nders/production-trends/

documentary-production/sources-of-nance

15 Australian Government (2016). It should be

noted that this also includes the radio and

internet services of the ABC and SBS, as

well as their transmission and distribution

services. As such, it is not a directly

comparable with the public support value

estimated in this report.

What are our stories worth? | Measuring the economic and cultural value of Australia’s screen sector

6

What are our stories worth? | Measuring the economic and cultural value of Australia’s screen sector

7

Deloitte Access Economic was commissioned by Screen Australia to estimate the economic and cultural

value of Australia’s screen sector. This study assesses the Australian screen sector’s contribution to

Australia through a number of dimensions, including its contribution to employment and gross domestic

product, to exports and tourism, and the audience and cultural value of Australian screen content.

The Australian screen sector is recognised as an enduring and dynamic component of the national

economy with close linkages to various economic inputs including skilled employment, digital technology

and innovation. Screen production alone stimulates signicant activity, employing numerous skilled and

creative workers, such as performers, designers, directors, producers and technical cast and crew. Further,

the screen sector can be viewed as an entire supply chain, from development through to distribution,

broadcast and retail, with each segment generating its own contribution to employment and economic

gross value add.

The screen sector also transcends economic benets, as the content that the sector produces can help

inuence and shape Australia’s cultural fabric and social identity. Images, ideas and experiences told by

the sector can help inform Australians about what it means to be Australian, their place in the world and

provides people with a set of shared stories that they can relate to.

1.1 Denition of the sector

The Australian screen sector is a large sector that spans the entire industry supply chain from production

to distribution and broadcast. Specic denitions have been developed for the purposes of the analysis

undertaken in this report. Firstly, the report denes the sector in terms of Broad and Core Australian content.

Secondly, it denes the economic activity categories across all segments of the Australian screen industry

supply chain.

1.1.1 Broad and Core content

Given that there is a vast range of types of screen content, both produced domestically and internationally, this

report denes two types of Australian screen content – Broad and Core Australian content.

Broad Australian content

This is lm and television screen content that is made under the creative control of Australians, including (but

not limited to) feature lm, documentaries, TV dramas, as well as a wide range of content such as news and

current aairs, light entertainment (e.g. The Project, Millionaire Hot Seat), reality shows (e.g. MasterChef Australia,

Australia’s Next Top Model, House Rules), lifestyle/food/travel shows and televised sports programs.

Core Australian content

This is screen content that is made under the creative control of Australians, which falls within the scope

of Screen Australia’s focus. Screen Australia’s focus is solely on Australian lm and television that has a scripted,

narrative focus as well as lm and TV documentaries. As such, Core Australian content sits within Broad content.

It includes Australia’s feature lms (e.g. Mad Max: Fury Road, The Dressmaker) and documentary lms (e.g.

That Sugar Film, Frackman). It also includes TV documentaries (e.g. First Contact, Go Back To Where You Came

From) and TV drama, which encompasses a diverse range of content, such as mini-series (e.g. The Secret River,

Catching Milat), drama shows (e.g. Wentworth, Underbelly), comedy shows (e.g. Upper Middle Bogan, The Family

Law) and children’s TV shows (e.g. Nowhere Boys, Totally Wild).

1. Introduction

What are our stories worth? | Measuring the economic and cultural value of Australia’s screen sector

8

Digital games

In addition to lm and TV content, the screen sector also includes digital games produced in Australia as well.

These include mobile and tablet games (e.g. Real Racing 3, Fruit Ninja, Crossy Road) and PC and console games

(e.g. Don Bradman Cricket, Rugby League Live 3).

Overall scope

All in all, the scope of this project is diverse and substantial, covering not only the areas of production that fall

within the interest of Screen Australia (and other screen agencies), but also the broader category of all lm

and television content that is produced under Australian creative control.

Figure 1.1 captures the distinction of Broad and Core screen content by format. Both Broad and Core screen

content can go through a variety of delivery channels, including TV, video and digital-only platforms.

Figure 1.1: Broad and Core screen content

News

Sports

Talk shows

Lifestyle/food/travel

programs, etc.

Core screen

content

Feature film

Drama TV

Documentaries

Digital

games

Broad Australian content

Under Australian creative content

Source: Deloitte Access Economics (2016)

1.1.2 Supply chain

The screen sector can be thought of as eight main sectors: production, distributors, exhibition (e.g. cinema),

free-to-air TV, pay TV, retail, rental and the online sector.

• Production: This encompasses content creation in lm and television products in Australia. It includes

pre-production activities, principal photography, as well as a wide range of post, digital and visual (PDV)

activities such as editing and applying computer generated imagery

• Distribution: The distribution subsector is the intermediary which provides an avenue between the

producers of screen content and television, retail, rental and cinemas

• Exhibition: The exhibition subsector provides cinema venues for the general public to view screen content

(primarily feature lms)

• Free-to-air TV: The free-to-air TV subsector is comprised of public (SBS and ABC) and commercial (Seven,

Nine and Ten) providers of broadcast television content. In the case of commercial networks, earnings

primarily come from advertising revenue

• Subscription TV: the subscription television sector provides television content to audiences via a

subscription-based service. This content is often more specialised and caters to smaller audience groups

• Retail: The retail subsector captures commercial retail activity involved in the sale of DVD and Blu-Ray

screen content

• Rental: The rental subsector captures commercial rental services which allow consumers to hire DVD and

Blu-Ray screen content

What are our stories worth? | Measuring the economic and cultural value of Australia’s screen sector

9

• Online: These are mainly internet-based video on demand (VOD) services for screen content and include

subscription video on demand (SVOD) services (such as Netix, Presto and Stan) and free online catch-up

services (such as ABC iview and TENPlay). Online does not include video-sharing websites such as YouTube,

which provide a range of professional web-based and user-generated screen content.

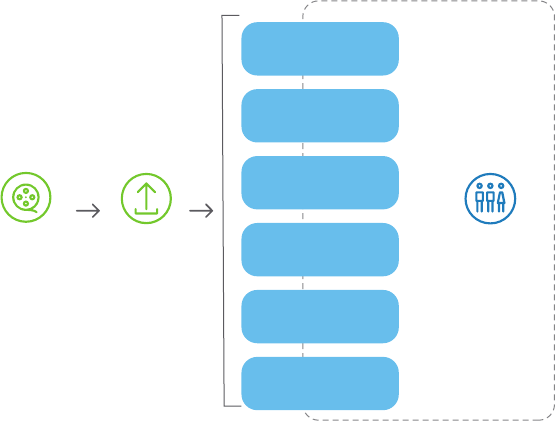

Screen content is created by the production subsector, enters the distribution subsector and is purchased by

audiences in the exhibition, free-to-air TV, pay TV, retail, rental and online subsectors (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2: The Australian screen industry supply chain

Audiences

Exhibition

Free-to-air TV

Pay TV

Retail

Rental

Online

Production

Distributors

Source: Deloitte Access Economics (2016)

This supply chain also includes other production activity undertaken by Australian companies, such as

production services for international “footloose productions” (e.g. Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Men Tell No

Tales lmed in Queensland) and post, digital and visual eects (PDV) services provided to foreign companies

(e.g. PDV work on Ted 2, The Avengers: Age of Ultron and The LEGO Batman Movie).

1.2 Framework for analysis

Deloitte Access Economics has developed a comprehensive framework to ensure that the research captures

the entirety of the contribution of Australian screen sector. A valuation methodology, consisting of four broad

parts is used. Further, in order to achieve these valuations, this report drew on other techniques such as

survey analysis and stakeholder consultations.

What are our stories worth? | Measuring the economic and cultural value of Australia’s screen sector

10

1.2.1 Valuation methodology

As shown in Figure 1.3, this report includes estimates of the value of the screen sector in terms of audience

value, economic contribution and cultural value.

Figure 1.3: Valuation methodology

Audience value

Film and TV delivers substantial

value to consumers in the form of

entertainment and leisure

Economic contribution

The economic contribution of Australian

film and TV is economic activities directly

attributable to Australian screen content

Cultural value

Australian-made screen

content has significant cultural

value and social importance

Source: Deloitte Access Economics (2016)

Audience value can be measured in two ways:

• Firstly, the value to audiences is equal to the revenue received from consumers plus any additional surplus

received by the consumer. These measures include total box oce revenue, consumer surplus and the

value of consumption choice

• Secondly, the value to audiences can also be measured by the value of time spent watching Australian

screen content.

Economic contribution quanties the value of production by a rm or industry in a historical reference year.

This was examined in terms of:

• Broad and Core screen content

• Footloose productions

• Digital games

• Screen exports

• Screen-induced tourism.

16

For example, excessive screen consumption may be associated with prolonged periods of inactivity which is linked to obesity;

screen content may depict subjects and imagery that is deemed to have potential social costs; and screen consumption may be

an addictive behaviour for some individuals, inducing them to potentially forego other activities they would like to engage in.

What are our stories worth? | Measuring the economic and cultural value of Australia’s screen sector

11

Cultural value can be captured through willingness-to-pay measures. For example, even those Australians

who do not regularly watch Australian lm or TV can place signicant “non-use” value on the existence of this

content. These include:

• The value of having the option to watch it in the future

• The value of others being able to watch it.

This report does not undertake a benet-cost analysis, and, therefore, does not consider the costs that can

be associated with screen consumption.

16

1.2.2 Survey analysis

To estimate the audience value and cultural value of Australian screen content, Deloitte Access Economics

elded a survey of domestic and international audiences. Approximately 1,000 domestic Australian

respondents and over 100 international respondents who had visited Australia, from New Zealand, the

United Kingdom, the United States and Canada, were surveyed for this report.

Domestic respondents were asked questions such as their willingness to pay and screen consumption

patterns of domestic audiences. This survey was also used to get a sense of the tourism impact of Australian

screen content from international respondents, and the data here was used to estimate the economic

contribution of screen-induced tourism.

1.2.3 Stakeholder engagement

To ll information gaps, gather practical insights into the sector and inform case studies, a series of

interviews was undertaken with a selection of organisations involved in the Australian lm, television,

and digital media industry. Nine stakeholder interviews were held with individuals who were able to provide

an informed view regarding the current economic and cultural contribution of the screen sector.

These consultations included stakeholders in the areas of production, lm distribution, documentary

lmmaking and digital distribution. The stakeholders interviewed are listed in Appendix A.

1.3 Structure of report

The report is divided into four main chapters of analysis, with each chapter looking at a specic area of

contribution, e.g. the sector’s economic contribution to exports and tourism, the audience value of the

screen medium, and the cultural value of the medium.

• Chapter 2 presents the economic contribution of the screen sector as classied by Figure 1.1 and Figure

1.2, in terms of its direct and indirect contribution to FTE employment, labour income, gross operating

surplus, and value add. This chapter also discusses the structural impacts of digital disruption and the rise

of digital screen content on the Australian screen sector

• Chapter 3 covers the contribution the screen sector makes to Australia’s export industry, in terms of export

income such as overseas royalties and license fees. Further, it examines the contribution the

sector makes to Australia’s tourism industry, in terms of promoting Australia internationally as a desirable

tourism location

• Chapter 4 explores the audience value of Australian screen content for domestic audiences. That is, how

much consumers value Australian content over and above what they pay (i.e., the consumer surplus) and

their willingness to pay, particularly for content that does not have a market price. This chapter also

discusses how digital screen content and digital technologies are altering the value of the content for

domestic audiences

• Chapter 5 covers the cultural and non-use value of the screen sector. These values can be estimated

through a survey and capture values that people may hold such as the valuing the existence of Australian

screen content and valuing the option to experience screen content.

What are our stories worth? | Measuring the economic and cultural value of Australia’s screen sector

12

2. Economic contribution analysis

This chapter presents the economic contribution of the screen sector, in terms of its direct and indirect

contribution to full-time equivalent (FTE) employment, labour income (total wage), gross operating surplus

(prots), and value add to the economy.

The estimates are presented for the:

• Broad screen sector

• Core screen sector

• Footloose production

• Digital games production.

Further, this chapter discusses the challenges and opportunities that the sector faces as a result of digital

disruption and the rise of digital screen content.

2.1 Economic contribution modelling

In this study, the total economic contribution of the Australian screen sector represents the sum of the

industry’s direct and indirect contributions.

The direct economic contribution of the screen sector is the value add created by labour and capital inputs

employed directly by the sector. In contrast, the indirect contribution is a measure of the demand for goods

and services produced in other sectors of the economy as a result of intermediate inputs demanded by the

screen sector (e.g. nancial services, electricity, rental services). The size of this ow-on activity is dictated by

the extent of linkages with other supplier sectors of the economy.

Value add, GOS and labour income

Value add can be thought of as the revenue earned by an economic entity (e.g. a company or sector) for

the goods and services it sells, excluding the cost of inputs it bought from other sectors. For example,

in the production subsector, a company applies its workers (e.g. cast and crew) and capital equipment

(e.g. studios and camera equipment) to goods and services supplied from other parts of the economy to

create products that are worth more.

The value add of an entity is comprised of the labour income that is earned by the workers it

employs and the gross operating surplus (GOS) which represents the prot that is earned by its

capital equipment. Value add excludes any subsidies that have been granted to the entity by the

government or similar public bodies.

All direct, indirect and total contributions are reported as value add and employment. Further detail on the

approach used to measure the economic contribution of the screen sector is discussed in Appendix E.

2.1.1 Data

The key data source was retail, box oce, production and recoupment data on Australian lm and television

content provided to Deloitte Access Economics by Screen Australia. This data covered Core documentary,

What are our stories worth? | Measuring the economic and cultural value of Australia’s screen sector

13

feature lm and drama television screen content supported by Screen Australia, but also covered broader

screen content as well. This data was particularly signicant in informing the gross revenue gures and

expenditure gures for the screen subsectors.

To supplement this data in the contribution modelling, other sources were used, including the Screen

Australia (2015a) Drama Report and data from the Screen Australia website on topics such as domestic box

oce performance, share of Australian cinema releases and Australian audiovisual royalties earned from

overseas sales.

Data was also drawn from the ABS datasets on lm, television and digital games industry in Australia for

2011-12 (ABS, 2013), from publicly available sales statistics from the Australian Home Entertainment

Distribution Association (AHEDA) and from various industry reports, such as IBISworld reports, and media

releases. This data was used to inform the overall cost structures and growth rates in key industry variables,

as well as determine the relative sizes of the Broad subsectors and Core subsectors. Finally, insights and data

provided during the stakeholder consultation process also served to validate the data incorporated and the

modelling estimates.

2.2 Contribution of screen sector

Previous studies have estimated the overall size of the Australian screen sector. For example, the Deloitte

Access Economics (2015a) report on the total economic contribution of the lm and television industry found

total value add to be around $5.8 billion in 2012-13.

17

Likewise, Deloitte Access Economics (2015b) found total

value add to be $77.2 million for South Australia’s screen production subsector alone.

This report, however, goes further and isolates the economic activity into lm and TV productions under

Australian creative control in terms of the Broad screen sector and the Core screen sector. It also isolates this

activity for footloose productions and for digital game production in Australia as well.

Australian TV content encompasses a wide range of production activity – it includes ctional or drama

production (such as mini-series, drama shows, comedy shows and children’s TV shows), as well as

factual documentaries. The remainder is allocated to content such as news, current aairs, light

entertainment, reality, and sport. In 2014-15, 47 TV drama programs (517 hours) were produced in

Australia, with expenditure of $299 million. The majority of these titles (and expenditure) were associated

with domestic programs.

Likewise, feature lm content in Australia covers a range of content – from ones with large international

releases to ones that have been domestic box oce and/or critical successes to more low-budget lms

and lms with limited local releases. In 2014-15, there were 35 Australian features released (including both

domestic productions and co-productions), representing $121 million of production expenditure.

2.2.1 The Broad screen sector

From 24-hour news to a vast array of sports coverage to countless lifestyle and reality shows, Broad

Australian screen content is highly prevalent. For example, in terms of television content, under broadcasting

regulations, all commercial free-to-air television licensees are required to broadcast an annual minimum

quota of 55% Australian content between 6am and midnight on their primary channel (ACMA, 2016a). They

are also required to provide during the same time at least 1,460 hours of Australian content on their non-

primary channels (ACMA, 2016a).

17

It is acknowledged that there is a dierence between the $5.8 billion gure from the 2012-13 estimates of Australian lm and

television and the gures estimated in this report. The dierence lies in two main areas: Firstly, the $5.8 billion gure covers a

larger remit of activity, including footloose as well as other content that is produced like advertising, which are not covered in

our report. Secondly, the data that was used in that modelling was older, whereas the ones in this report are considerably more

up-to-date and robust.

What are our stories worth? | Measuring the economic and cultural value of Australia’s screen sector

14

Australian content features quite heavily for the public free-to-air channels. For example, according to the

consultation with the ABC, 10-15% of children’s content on ABC Kids is Australian-made, as is 45% of prime-

time content on ABC1 and ABC2. Further, in terms of content commissioned by the ABC, Australian content

made up approximately 50% of their commissioned hours and 70% of their budget.

Further, pay TV is also regulated by a compulsory standard which requires a minimum expenditure of 10% on

Australian dramas on their drama channels, although this can also be covered by their expenditure in other

content such as feature lms (ACMA, 2016b). This also ensures some level of Australian content is present on

subscription-based television channels, notwithstanding other types of locally produced content on pay TV,

from Australian lifestyle shows to news programs.

Economic contribution

The Broad screen sector in Australia had a total estimated economic contribution of approximately

$2.6 billion in value add to Australia’s GDP and 20,158 FTE jobs to national employment in 2014-15.

This total value add is the equivalent of around 5% of Australia’s information media and telecommunications

industry or around 18% of its arts and recreation services industry.

18

Value add is the sum of GOS and labour income, minus any subsidies. The total gures presented below in

Table 2.1 are the summation of the total direct gures and the indirect gures.

Table 2.1: Economic contribution of all Broad screen sectors, 2014–15

GOS ($m) Labour income ($m) Value add ($m) Employment (FTE)

Direct 649.1 1,259.6 1,825.5 13,151.2

Production* 84.8 492.0 493.6 6,558.0

Distribution 92.9 36.9 129.8 432.0

Free-to-air TV 277.9 519.4 797.3 3,64 6.1

Pay TV 165.3 178.9 344.2 1,649.6

Exhibition 8.4 9.5 17.9 275.9

Retail 8.0 14.5 22.5 450.7

Rental 4.2 4.9 9.1 109.0

Online 7.7 3.5 11.2 30.0

Indirect** 296.4 444.8 741.2 7,007.1

Total 945.6 1,704.4 2,566.8 20,158.4

Source: Deloitte Access Economics (2016). Due to rounding, gures may not add up to totals.

*Due to subsidies, value add is less than GOS and labour income

**Indirect gures refer to production only.

In terms of employment, the production subsector made the largest contribution, directly employing

6,558 FTEs. This was followed by free-to-air TV with around 3,646 FTE jobs and pay TV with around

1,650 FTE jobs. In terms of direct value add, the largest contribution came from the free-to-air TV

subsector with around $797 million in value add, with the production subsector next at around $494 million

in value add. The pay TV subsector also made a signicant contribution with $344 million in direct value add.

18

It is acknowledged that there is a dierence between the $5.8 billion gure from the 2012-13 estimates of Australian lm and

television and the gures estimated in this report. The dierence lies in two main areas: Firstly, the $5.8 billion gure covers a

larger remit of activity, including footloose as well as other content that is produced like advertising, which are not covered in

our report. Secondly, the data that was used in that modelling was older, whereas the ones in this report are considerably more

up-to-date and robust.

What are our stories worth? | Measuring the economic and cultural value of Australia’s screen sector

15

The smallest contribution, in terms of both value add and employment, for Broad screen content was made

by the online and rental subsectors. The small size of the rental subsector very much reects the declining

popularity of video rental. Analysis of AHEDA statistics on rental wholesale of all video formats, over the ve

year period leading to 2012-13, shows that total sales fell overall by 65%. In contrast, online platforms are

small due to starting o from a small base, but are anticipated to grow, with rapid domestic uptake following

the introduction of the SVOD services Netix, Presto and Stan in 2015.

19

In order to avoid any double counting, the indirect contribution gures provided here are for the production

subsector only (reecting that numerous shared resources across the screen content supply chain).

20

The role of advertising

Although not examined in this chapter in terms of its economic contribution, the advertising industry

also plays an important role with regards to Australian screen sector activities. Firstly, it funds a

signicant amount of Broad and Core screen content, such as through advertising revenue earned by

free-to-air TV broadcasts. According to ZenithOptimedia forecasts, Australia’s television advertising

revenue is expected to reach just under $4 billion in 2016 (Mason, 2016).

It is also an important adjacency to the production subsector, as cast and crew employed in the Broad

and Core screen sector also earn income from advertising work and many technical and creative screen

professionals that eventually end up in Australian lm and TV productions were initially trained through

working on advertisements.

On free-to-air television, Australian produced content dominates in terms of ratings. According to

consolidated OzTam ratings data across ve metropolitan markets (Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane,

Adelaide and Perth), the highest rated non-sports shows were the nal episodes of MastercChef, My

Kitchen Rules and The Block, with 2 million views and over (Knox, 2016a). Given these high ratings, it is

apparent that Australian content is associated with a large amount of advertising revenue which accrues

to the commercial free-to-air television subsector.

2.2.2 The Core screen sector

According to the Drama Report (Screen Australia, 2015a), the total domestic spend for Australian feature lm

and drama TV was $420 million in 2014-15, amounting to a total of 82 titles. Breaking this down, $121 million

was spent on 35 feature lm titles and $299 million was spent on 47 drama TV titles.

The Australian screen sector produces a substantial amount of broader screen content. As such, the

economic contribution gures in this section tend to be smaller as these numbers focus on the supply chain

of Australian content solely in the realm of feature lm, drama TV and documentaries.

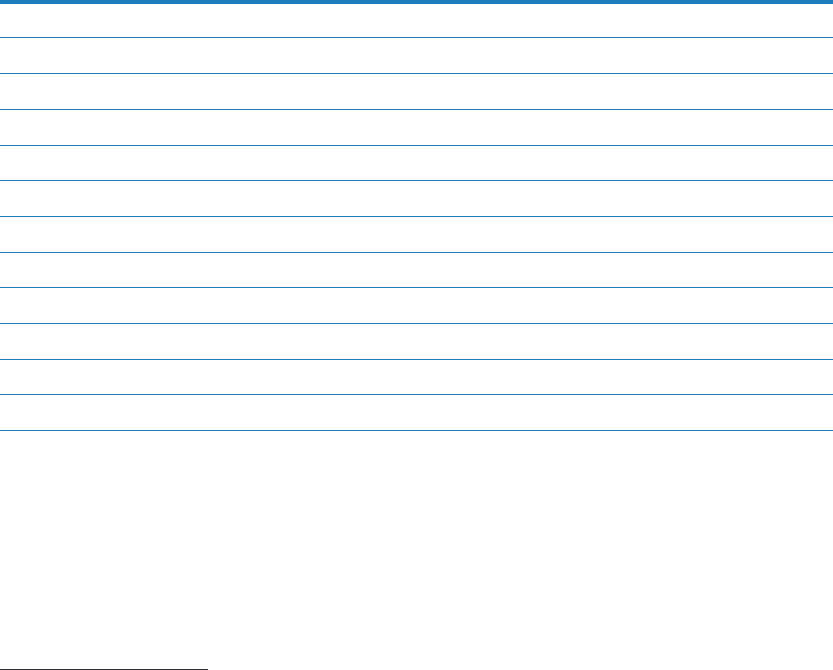

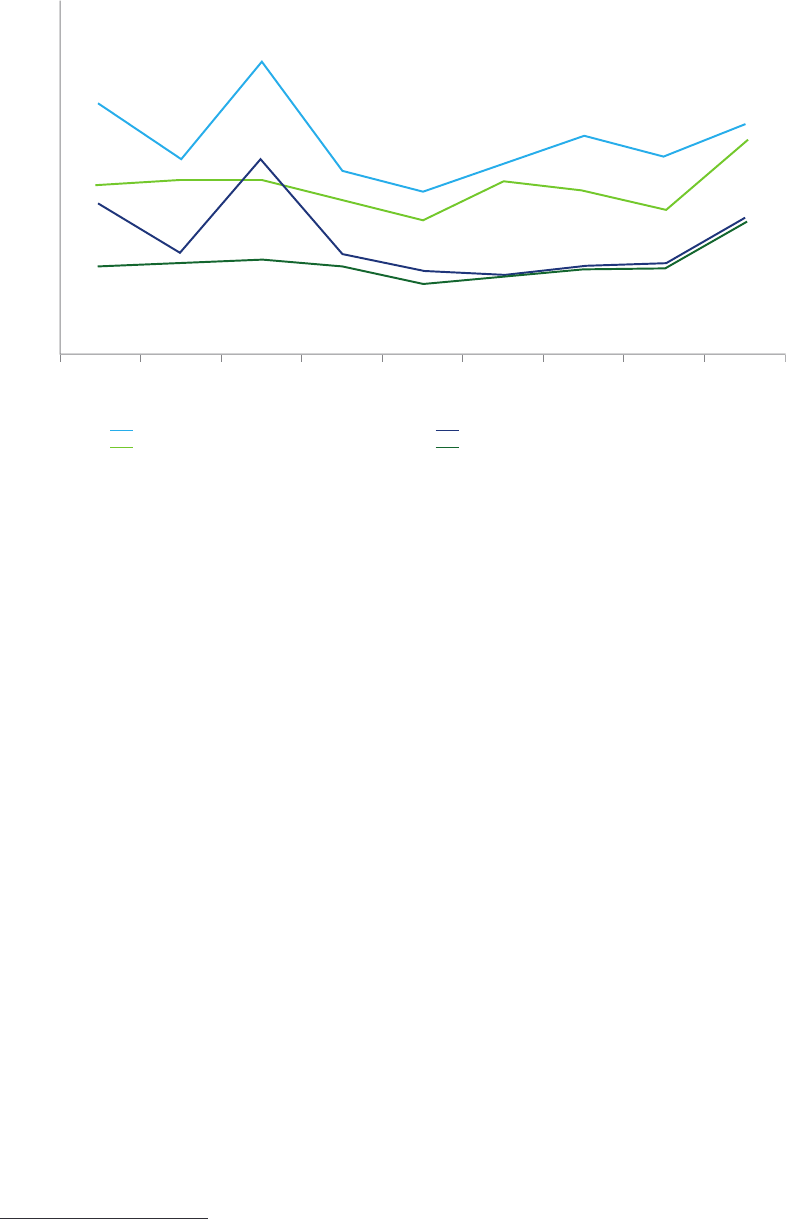

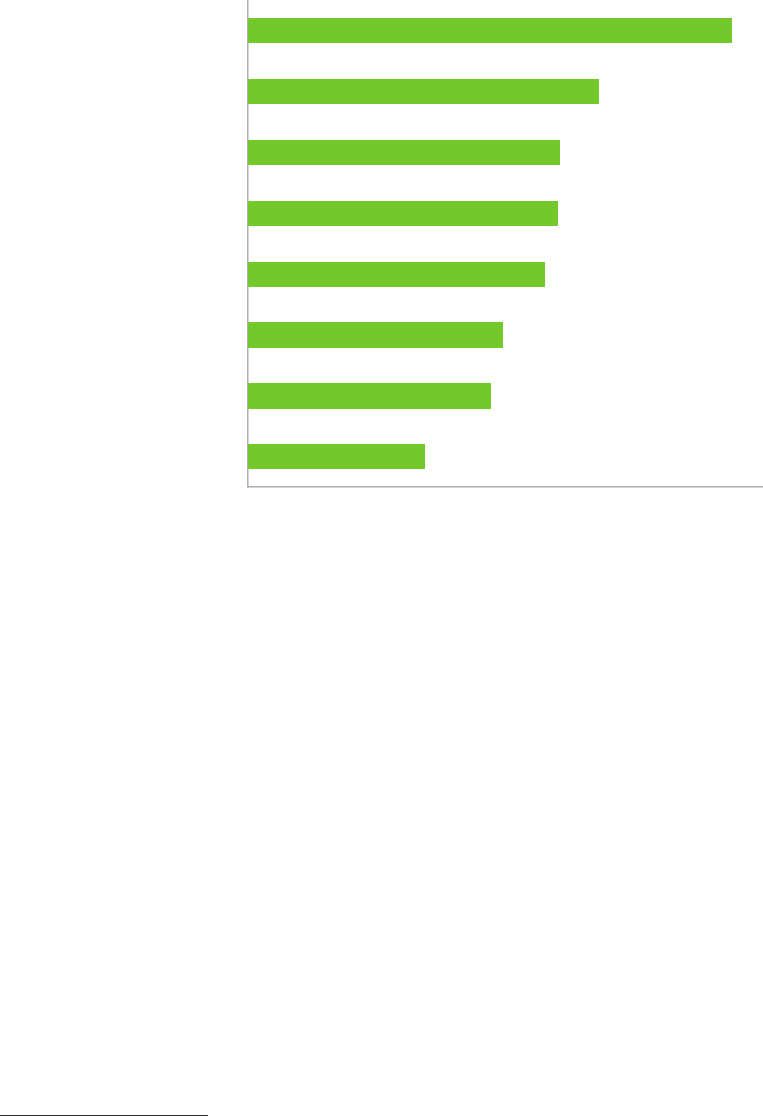

Over the last few years, Australian TV drama expenditure has been higher than Australian feature lm

expenditure and has been relatively more stable, with spending on feature lms uctuating more signicantly

in comparison (Chart 2.1). The ve year average domestic spend (2010-11 to 2014-15) for feature lm has

been $213 million while the ve year average domestic spend for drama TV has been $329 million – which

makes 2014-15 a relatively low year in terms of feature lm and drama TV domestic spending.

19 Domestic uptake of SVOD has grown rapidly despite a number of these services only being introduced to Australia in 2015. By

May of 2016, nearly 6.2 million Australians over the age of 14 had access to SVOD services in their homes, representing a total of

over 2.3 million home subscriptions (Roy Morgan Research, 2016).

20 This most likely provides a conservative estimate of the indirect contribution of the screen sector, given that other subsectors

may also demand domestic intermediate inputs which are not used by other subsectors.

What are our stories worth? | Measuring the economic and cultural value of Australia’s screen sector

16

Chart 2.1: Total domestic feature lm and TV drama expenditure, 2010–11 to 2014–15

400

350

300

250

200

150

100

50

0

2010-11 2010-12 2012-13

Financial year

Features TV drama

2013-14 2014-15

Expenditure ($m)

Source: Deloitte Access Economics (2016) based on Screen Australia (2015a) Drama Report’s feature lm and TV drama

expenditure data.

Further, in the documentary space, the total production budget for 2014-15 was $147 million and 184 titles

were produced, of which 97 were single titles and 87 were for documentary series. In terms of production

budget, this is not far o from the ve year average production budget (2010-11 to 2014-15) of $144 million.

Economic contribution

In terms of all eight subsectors involved with Core Australian content in 2014-15, the total economic

contribution was $847 million in value add to Australia’s GDP and 7,650 in FTE jobs to national

employment (Table 2.2). This total value add is the equivalent of around 7% of Australia’s arts and

recreation services industry.

Table 2.2: Economic contribution of all Core screen sectors, 2014–15

GOS ($m) Labour income ($m) Value add ($m) Employment (FTE)

Direct 206.1 420.7 543.5 4,782.6

Production* 34.7 201.3 152.8 2,683.6

Distribution 38.0 15.1 53.1 176.8

Free-to-air TV 74.0 138.2 212.2 970.3

Pay TV 44.0 47.6 91.6 439.0

Exhibition 8.4 9.5 17.9 275.9

Retail 3.3 5.9 9.2 184.4

Rental 1.7 2.0 3.7 44.6

Online 2.0 0.9 3.0 8.0

Indirect** 121.3 182.0 303.3 2,867.4

Total 327.4 602.7 846.9 7,650.0

Source: Deloitte Access Economics (2016). Due to rounding, gures may not add up to totals.

*Due to subsidies, value add is less than GOS and labour income

**Indirect gures refer to production only.

As with Broad screen, Core screen content production remains the largest direct employer and free-to-air TV

What are our stories worth? | Measuring the economic and cultural value of Australia’s screen sector

17

generates the largest direct value add, while the rental and online subsectors provides the smallest

economic contribution.

In terms of employment, the production subsector – through its creation of Australian feature lm, drama

TV and documentaries – made the largest contribution, directly employing around 2,684 FTEs. This was

followed by free-to-air TV with around 970 FTE jobs and pay TV with 439 FTE jobs.

In terms of direct value add, the largest contribution came from the free-to-air TV subsector with around

$212 million in value add, with the production subsector next at $153 million in value add. Not counting for

government subsidies in Australian Core screen content production, the sum of capital and labour earnings

in the production subsector (i.e. the sum of GOS and labour income) exceeds that of all other subsectors. The

pay TV subsector also made a signicant contribution with $92 million in direct value add.

The direct economic contribution of production is smaller for Core content than for Broad – $153 million

and 2,684 FTE jobs for Core compared to $494 million and 6,558 FTE jobs for Broad. The direct economic

contribution of subsectors such as free-to-air TV and pay TV are also signicantly smaller as well.

Because the exhibition subsector deals only with Core screen content, namely feature lm and documentary

lms, its economic contribution (around $18 million in direct value add and 276 in direct FTE jobs) for Core

screen content is the same as for Broad screen content.

One notable change in relative sizes among subsectors is that the Core retail subsector, in terms of both

direct value add and employment, is smaller than the exhibition subsector, in contrast to being larger than

the exhibition subsector for Broad retail.

2.2.3 Footloose production

Footloose production refers to television and lm production activity which can be placed and located in

many dierent locations. This applies particularly to large budget, international studio nanced productions

that choose to lm in Australia instead of elsewhere.

In 2014-15, the total expenditure (both production and PDV-only activity) spent by footloose productions in

Australia was $418 million according to the Screen Australian Drama Report (2015a). This comprised $397

million in foreign features (including Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Men Tell No Tales, the largest international

feature ever to shoot in Australia) and $21 million in foreign TV drama activity. It should be noted that 2014-15

was unusual in terms of how high foreign expenditure was, with the ve year average being $196 million from

2010-11 to 2014–15.

Economic contribution

Much of the growth in footloose production in 2014-15 was driven by the presence of the Pirates of the

Caribbean production in Queensland. These large international opportunities vary over time in terms of

frequency and size and their presence in Australia can depend on a number of external factors, including

exchange rates, tax incentives and the lming decisions of international studio companies. As such, these

economic contribution gures can best be seen as supportive of the sustainability and growth of the

domestic Broad and Core screen sector.

The total economic contribution of footloose activity in Australia in 2014-15 amounted to $382 million in

total value add and 4,093 in FTE jobs.

18

Table 2.3: Economic contribution of the Australian production subsector from footloose activity, 2014–15

GOS ($m) Labour income ($m) Value add ($m) Employment (FTE)

Direct 9.5 148.4 158.0 1,978.8

Indirect 89.4 134.2 223.7 2,114.3

Total 99.0 282.7 381.6 4,093.0

Source: Deloitte Access Economics (2016). Due to rounding, gures may not add up to totals.

The indirect economic contribution is a signicant component of the total economic contribution, generating

a higher value add and level of employment through ow-on eects in the economy than the direct value add

and employment generated by footloose productions Australia.

One thing to note is that labour income makes up the majority of value add. This is due to the fact that

footloose productions primarily hire Australian cast and crew as labour input, with any prots accrued (i.e.

the gross operating surplus) from these activities going to the overseas production studios.

2.2.4 Digital games

At present, Australian game developers are predominantly small- to medium-sized independent studios

and studios of international publishers that produce game content for mobile phones, tablets, PCs and, to

a lesser extent, consoles. These games are primarily exported to the international market. According to the

GDAA (2015), there are currently 225 game development businesses in Australia.

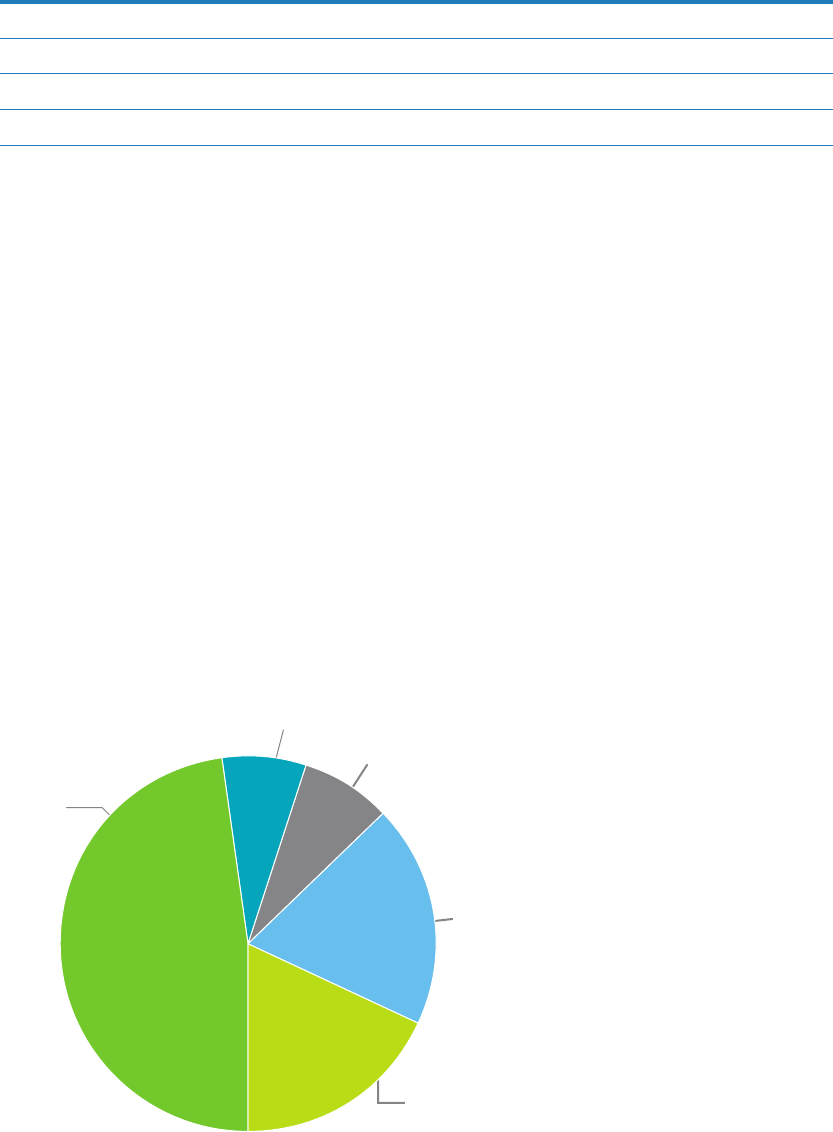

The majority (48%) of the 225 current Australian game development businesses are located in Victoria

with the next two largest centres being Queensland (19%) and New South Wales (18%) (GDAA, 2015). This is

illustrated below in Chart 2.2.

Chart 2.2: Geographic spread of Australian game development businesses

South Australia

8%

Victoria

48%

Western Australia

7%

Queensland

19%

New South Wales

18%

Source: Deloitte Access Economics (2016) based on GDAA (2015)

What are our stories worth? | Measuring the economic and cultural value of Australia’s screen sector

19

Digital games consumption in Australia

The consumption of digital games is growing strongly in Australia. In 2015, revenues from the sale

of gaming-related goods (which includes games, subscriptions, hardware and accessories) reached

an estimated $2.83 billion, an increase of 15% over retail revenue of 2014 (IGEA, 2016). In addition,

digital sales in 2015 ($1.59 billion, up 27% from 2014) exceeded traditional retail sales ($1.24 billion,

up 2% from 2014).

According to the Digital Australia Report 2016 (IGEA, 2015), video game consumption is highly prevalent

in Australian households. Around 98% of homes with children under eight have a device for playing

computer and video games. Of all homes, nine in 10 have game devices in use. The percentage of

households with games has grown from around 75% in 2005 to over 90% in 2015, demonstrating that

this is a mature media market.

Economic contribution

In 2014-15, the total economic contribution of digital game production in Australia was around $123 million

in value add and 1,053 in FTE jobs. This gure relates to the production of digital games alone and does not

include publishers/distributors and retail, rental or online subsectors that are further along the value chain

for the Australian games sector.

Table 2.4: Economic contribution of the digital game production subsector, 2014–15

GOS ($m) Labour income ($m) Value add ($m) Employment (FTE)

Direct 46.8 50.7 96.6 844.2

Indirect 10.4 15.8 26.2 208.2

Total 57.2 66.5 122.7 1,052.4

Source: Deloitte Access Economics (2016). Due to rounding, gures may not add up to totals.

The digital game production subsector also generates a much larger direct value add and employment

gure than through indirect ow-on eects in the Australian economy. Much of this relates to digital game

production being a technical and creative industry requiring high-skilled workers generating complex

software products. For example, in 2015 there were 37 tertiary providers in Australia oering 172 games or

games-related courses (GDAA, 2015). In many instances, this process – while costly and intensive in terms

of direct capital, labour inputs and imported intermediate inputs – does not source the majority of its

intermediate inputs from domestic suppliers in Australia.

2.3 Benets and challenges facing the sector from digital disruption

It is important to recognise that the rise of digital screen content and its supporting technologies such as

video on demand has changed how value accrues to Australian suppliers and distributors. These changes are

bringing signicant structural changes to the whole screen sector.

In this report, digital screen content is dened as consisting of traditional content made for traditional

distribution that is digitally distributed, as well as online originals which are professional web-based

productions made specically for online viewing.

21

21

Another form of digital screen content is user-generated content that is produced and uploaded to video-sharing sites

and social media by everyday users, usually without any intention to earn revenue. This encompasses an immense variety of

screen content and is a rapidly growing form of content creation. However, for the purposes of this report on the Australian

screen sector, this chapter will focus only on traditional content and online originals as they are more closely associated with

traditional screen sector activity.

What are our stories worth? | Measuring the economic and cultural value of Australia’s screen sector

20

One on hand, digital screen content brings benets such as heightened potential for audience reach and potential

cost-savings associated with delivering screen content. On the other hand, it has altered the traditional revenue

stream of Australian lm and TV subsectors and made content monetisation more complex.

2.3.1 Benets for producers and distributors

Dissemination of content

A major appeal of digital distribution is that the audience for content is now potentially global. Dissemination

is helped by the fact that video on demand services makes it easier for niche screen content to be

distributed. Without restrictions such as broadcast or cinema schedules, a wide range of content can be

distributed. Likewise, it bypasses distribution bottlenecks and physical costs (such as the storage and

transport of DVD/Blu-Ray).

Opportunities for new and niche content creators

Digital distribution can benet new entrants and niche content creators in the production subsector, allowing

them sell their content earlier than otherwise. These companies can grow an audience base in a shorter span

of time, without needing to rely heavily on intermediaries such as major distributors, cinema operators and

television broadcasters to reach potential audiences.

There are also opportunities for audience-driven business models, where online content with a strong

following can become self-sustaining productions. An example of this was the comedy series The Katering

Show which was initially released on YouTube in 2015, before being picked up and partly funded by the ABC

for a second series on iview in 2016.

Digital disruption brings with it opportunities to engage new markets

While Australian content may face challenges domestically, advances in digital technology bring with it

opportunities to engage new markets overseas. Data provided by Screen Australia for the 2014-15 sample

period shows that 39 Australian titles are available for rent, own or subscription via 323 VOD sources

both domestically and abroad. Over 50% of these titles have reached international audiences, with nearly

20 countries other than Australia able to access Australian content on VOD. This provides insight into the

revenue raising potential of Australian content via digital platforms to international markets.

2.3.2 Challenges for producers and distributors

Loss of traditional ancillary markets

Content has been typically released through one delivery channel for a set period of time (“release window”)

before it can be released via other delivery channels. This can benet Australian content – for example, even

if a local lm struggled to cover costs at the box oce, other outlets such as video, subscription TV and free-

to-air TV have served as ancillary markets, giving the lm alternative revenue streams.

Digital disruption has greatly aected the viability of monetisation through ancillary markets. The retail

subsector is experiencing falling sales due to competition from online and Australian content is experiencing

lower licensing fees in the TV subsectors. This is in part due to competition with SVOD and, in the case of

free-to-air TV, changes to prime time show composition in order to attract advertising revenue (Screen

Australia, 2015b). The alternative to the erosion of ancillary markets is to focus solely on digital distribution.

But Australian content that is predominantly released online have yet to reach the consistent levels of

monetisation provided by traditional release chains.

Release windows becoming more complicated

Greater monetisation is possible through creative windowing arrangements, such as having the content

shown for a window of time on a SVOD or catch-up service around the same time as it is shown by free-to-air

broadcasters, in cinemas or on pay TV. However, the ability to monetise content and sell the content rights

What are our stories worth? | Measuring the economic and cultural value of Australia’s screen sector

21

in hybrid arrangements is constrained by the fact that negotiating creative windowing can be costly. The

framework for purchasing the right to broadcast content in the current environment of multi-channel and

online streaming has led to ongoing complexities for the screen sector.

Uncertainty around dominant SVOD services

Australian-based producers are faced with the challenge of signicant content saturation, having to compete

with a large quantity of easily accessible international content. It remains to be seen whether dominant SVOD

services will support the viability of the local production subsector.

22

Need for better data analytics and reporting

One challenge to creating a successful monetisation strategy is a need for better data and measurements

analogous to box oce revenue and television ratings that can provide insight into the performance of

Australian content in a digital environment (Screen Australia, 2015b). There are also untapped opportunities

for data analytics to drive value for producers and distributors. The consumption of digital screen content

generates large amounts of data on consumer behaviour which can provide valuable insight on how to

improve the audience reach and audience engagement with their content, as well as address advertising

revenue challenges.

Online originals

Online originals – that is, screen content that is professional produced specically for online platforms

– is quickly becoming a signicant part of the Australian screen sector. For example, ABC iView has

begun to commission short-form online original content to engage with online-orientated audiences

and help support Australia’s emerging digital production subsector (Knox 2015; 2016b). According to

consultations with the ABC, these emerging talents have experience producing content that resonates

with audiences more attuned to online video formats. By engaging with them, the ABC is seeking to learn

from their productions techniques.

Recent examples of well-received online original shows include The Katering Show, Starting From… Now!,

Fragments of Friday and The Wizards of Aus. Overall, online originals are an evolving and rapidly growing

part of the screen sector.

2.4 Summary

In summary, in Australia in the reference year 2014-15:

• The Broad screen sector made a total economic contribution of approximately

$2.6 billion in value add and 20,158 FTE jobs

• The Core screen sector made a total economic contribution of

$847 million in value add and 7,650 FTE jobs

• Footloose activity made a total economic contribution of

$382 million in total value add and 4,093 FTE jobs

• The digital game production subsector made a total economic contribution of

$123 million in value add and 1,053 FTE jobs.

22 That being said, Australia’s main SVOD services have begun to invest in original Australian content. For example, Screen

Queensland recently announced a partnership with Stan to develop and nance a feature lm to be distributed exclusively

on the service (Queensland Government, 2016). Stan has also commissioned a season of the comedy series No Activity

and invested in the television show Wolf Creek (Media Day, 2015).

What are our stories worth? | Measuring the economic and cultural value of Australia’s screen sector

22

Figure 2.1: Total economic contribution of Broad and Core screen content

$2,567 million

in value add

20,158 FTE job

Core screen

content

$847 million

in value add

7,650 in FTE job

Broad Australian content

Digital games

Under Australian creative control

$123 million

in value add

1,053 FTE job

Source: Deloitte Access Economics (2016)

Table 2.5 below provides the list of full estimates for the 2014-15 direct economic contribution of the

Broad screen sector, Core screen sector, footloose production subsector and the digital games production

subsector. It includes standard estimates such as value add and employment, as well as estimates of

revenue, intermediate inputs, subsidies and taxes.

23

Table 2.5: Full direct economic contribution estimates, 2014–15

Broad

(All)

Core

(All)

Footloose

(Production)

Digital games

(Production)

Gross revenue ($m)

24

7,248.9 2,294.6 418.0 127.2

Direct value add ($m)

25

1,825.5 543.5 158.0 96.6

GOS ($m) 649.1 420.7 9.5 46.8

Taxes on production ($m) 223.8 61.6 1.6 1.5

Labour income ($m) 1,259.6 206.1 148.4 50.7

Excluding subsidies ($m) -83.2 -83.2 - -0.9

Intermediate inputs ($m) 5,043.8 1,586.3 257.9 28.1

Subsidies ($m) 83.2 83.2 - 0.9

Taxes on products ($m) 296.3 81.6 2.1 1.7

Direct employment (FTE) 13,151.2 4,782.6 1,978.8 844.2

Source: Deloitte Access Economics (2016).

23 Gross revenue estimates are collected from a variety of sources, such as data provided by Screen Australia and from industry

reports. Intermediate inputs were estimated from the percentage of total industry expenses for the relevant subsectors as

reported by the ABS and other sources. Subsidies came from the Screen Australia (2015a) Drama Report. Taxes on production

and products were estimated from the tax split reported by the ABS Input-Output tables for the relevant subsectors. A

summary of government subsidies, as well as other forms of government support not included in Table 2.5, is provided in

Appendix B.

24 Gross revenue is equal to direct value add, intermediate inputs, subsidies and taxes on products.

25 Direct value add is equal to GOS (EBITDA) and labour income, minus subsidies. Taxes on production are included in direct value

add under GOS.

What are our stories worth? | Measuring the economic and cultural value of Australia’s screen sector

23

3. Exports and tourism

This chapter examines the economic contribution of Australian screen content in terms of screen content

exports and screen-induced tourism. This chapter provides:

• An overview of export earnings for lm and television

• An estimate of 2014-15 export earnings for Core Australian content

• A discussion of how screen content can induce tourism

• An estimate of the overall value of screen-induced tourism in Australia.

3.1 Export earnings for lm and television

Exports of Australian lm and television to international markets occur primarily through distributors. For

example, ABC has ABC Commercial which delivers screen content internationally. Examples of ABC exports

include Miss Fisher’s Murder Mysteries and The Code which has been shown in a number of countries, such as in

the United Kingdom, Canada and France, among others.

Further, according to ASTRA (2015), in 2014-15, pay TV providers exported a total of 13,199 hours of

Australian content overseas for foreign audiences. Likewise, a number of recent Australian lms have also

been exported overseas in the last year, including The Dressmaker, The Water Diviner and – perhaps, most

signicantly – Mad Max: Fury Road, which was highly successful at the international box oce.

3.1.1 Audiovisual royalties in previous years

Screen Australia releases data on royalties earned and paid by Australia for international screen content

(Screen Australia, 2016a). This data is drawn from unpublished data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics

(ABS), Balance of Payments and International Investment Position (cat. no. 5302.0), and reports the value of

royalties arising from export of cinema, television, video (Blu-ray, DVD and VHS) and multimedia releases.

26

In 2013-14, total foreign royalties earned in cinema, television, video and multimedia releases amounted to

$199 million. In contrast, total foreign royalties paid were $1.36 billion. When imports are accounted for,

Australia has had a persistent annual decit in audiovisual trade since 1991-92. One exception to this decit

was in 2000-01 when television royalties earned by the Sydney Organising Committee for the Olympic Games

(SOCOG) created Australia’s rst ever screen royalty trade surplus of $552 million.

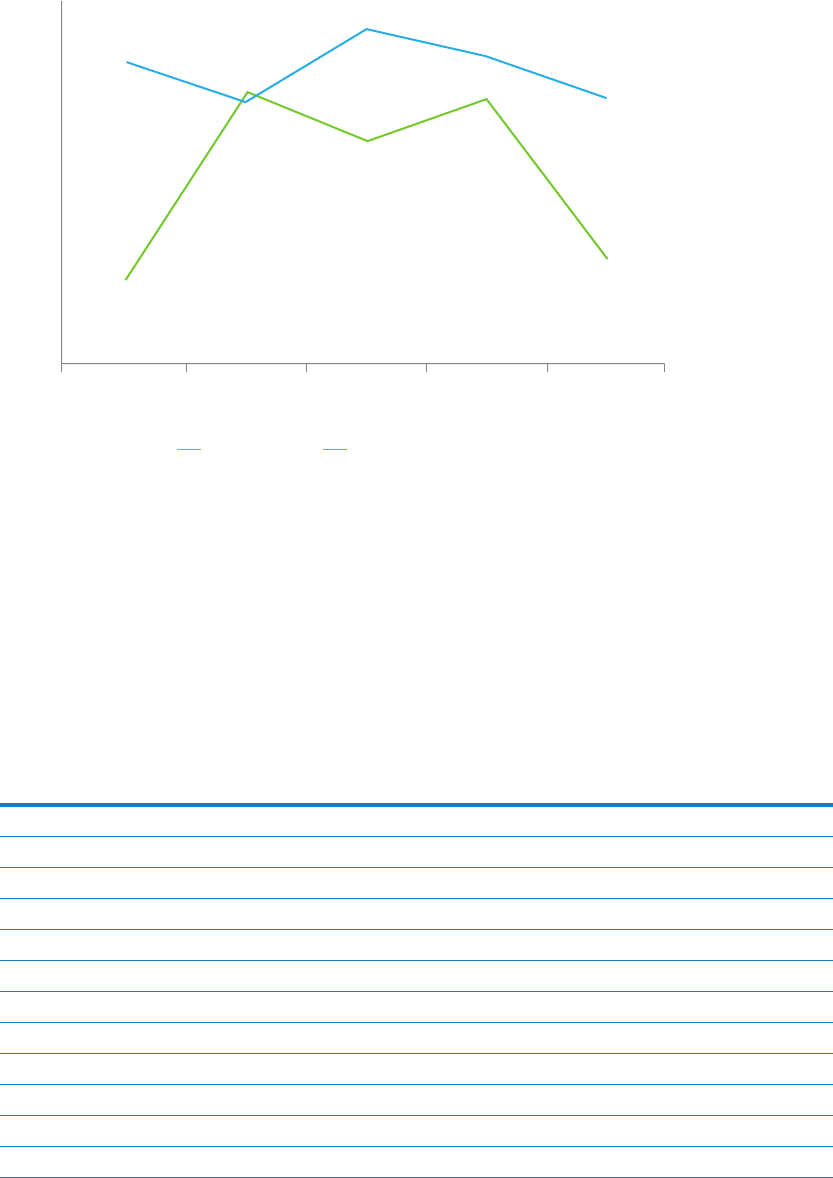

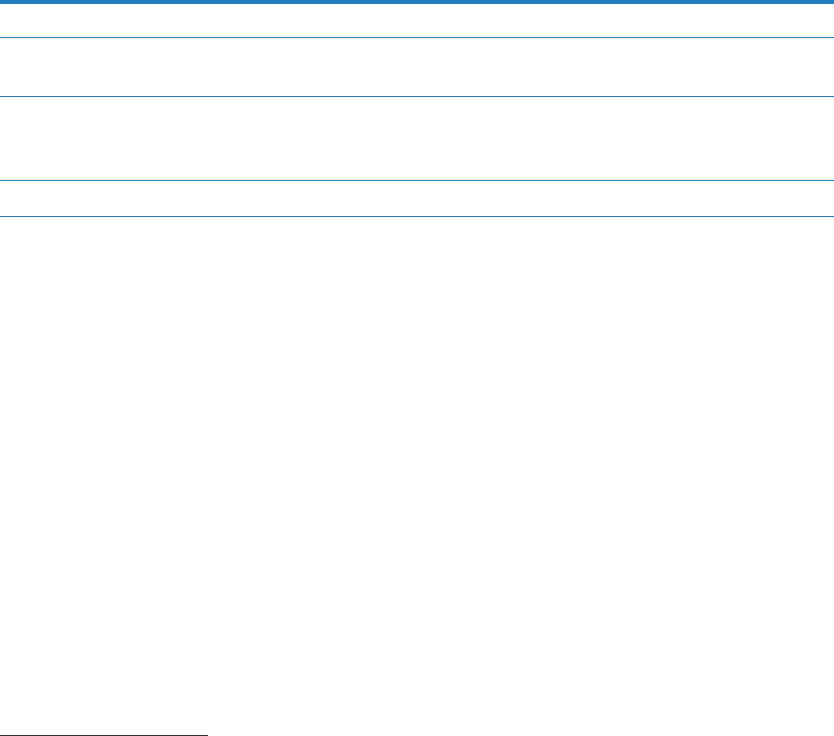

As shown below in Chart 3.1, the movement of total royalty earnings appears to be driven primarily by

television exports (particularly between 2005-06 and 2009-10, and from 2012-13), with rises and falls in

television exports contributing heavily to rises and falls in total screen exports. These television royalties also

include earnings from feature lms sold for overseas television screenings.

Furthermore, as shown in the chart, the majority of total royalty earnings and television royalties are to the

OECD nations (e.g. UK, US, Canada, New Zealand). This is to be expected given that OECD countries have

higher average levels of disposable household income and some are Anglophone countries with culture,

heritage and language comparable to that produced in Australian screen content.

26

It is important to note that the ABS also reports gures for unidentied audiovisual imports and exports – this is included

in the total royalty gures, but is not captured in their separate reporting of television, cinema, and video. Further, for

certain years and for certain export destinations where the data is unpublished due to condentiality reasons.

What are our stories worth? | Measuring the economic and cultural value of Australia’s screen sector

24

Chart 3.1: Total and television royalty earnings, OECD and all territories, 2005–2014

300

250

200

150

100

50

0

2005-06 2006-07 2007-08 2008-09

Financial year

Total screen royalities (All territories)

Total screen royalities (OECD)

2009-10 2010-11 2011-12 2012-13 2013-14

$m

Total screen royalities (All territories)

Total screen royalities (OECD)

Source: Deloitte Access Economics (2016) based on Screen Australia (2016a) data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics

(ABS), Balance of Payments and International Investment Position (cat. no. 5302.0).

While year-to-year royalty earnings from abroad are volatile, from 2005-06 to 2013-14, total royalties earned

from all territories have grown by 2% on average per year and total royalties earned from the OECD nations

have grown by 4% on average per year. Further, analysis of publicly available data on international royalties

reveals that from 2005-06 to 2013-14, average annual television royalty earnings were around $99.2 million.

In contrast, the average for cinema was $5 million, and the average for video was $4.1 million.

27

3.1.2 Total lm and television export earnings

International royalty earnings alone, however, do not capture the full scope of lm and television export

earnings for the screen sector. Along with royalties, lm and television also generates other export products

in the form of international pre-sale of television shows.

Below are the types of export earnings which can accrue to Australian lm and television content:

• Foreign box oce earnings – e.g. the international box oce earnings for The Dressmaker, which was

released in countries such as Argentina and the UK, or The Water Diviner, which was released in countries

such as Turkey and the US

• License fees to foreign television broadcasters or video sell-through, video-on-demand, etc. – e.g.

licensing earnings from Neighbours being broadcast on Channel 5 in the UK or Wentworth being added to

Netix in the United States

• DVD/Blu-ray/other format retail sales overseas – e.g. international DVD sales of the television series The

Slap or international Blu-ray sales of Mad Max: Fury Road.

27 Noting that 2012-13 and 2013-14 export gures for video are unpublished.

What are our stories worth? | Measuring the economic and cultural value of Australia’s screen sector

25

Core screen content export earnings for 2014–15

Drawing on a number of data sources, including gross box oce and recoupment data provided by Screen

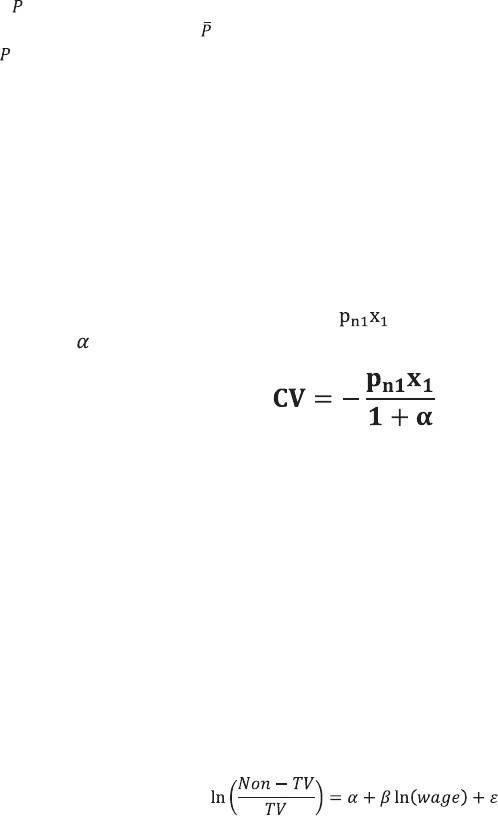

Australia, the total screen export earnings for Core screen content were estimated for the reference year